ABSTRACT

Youth offenders with high levels of callous unemotional (CU) traits are characterized by a lack of empathy and deficits in emotionality that in turn depict a pattern of consistent and violent antisocial behavior. This review aims to identify the impact of the criminal justice involvement in male youths who score high on callous unemotional traits in order to develop comprehensive intervention methods. Offending behavior among adolescents who are high on CU traits tends to be more frequent with a high degree of violence and has lasting influences amongst peers. To test the hypothesis that CU traits lead to higher involvement in crime among adolescents who have previously been in contact with the criminal justice system (CJS), a systematic literature review is conducted to assess prior empirical knowledge on this relation and identify potential uses for treatment. Overall findings indicate that contextual factors, such as neighborhood disorganization, maternal warmth, and a high trusting therapeutic-alliance relationship act as protective factors that mitigate the detrimental effects of severe delinquency and antisocial behavior on youth offenders with high levels of CU.

Keywords: Callous Unemotional traits (CU traits), Youth Delinquency, Adolescent Offenders, Juvenile Justice System, Antisocial Behavior, Recidivism, Conduct Disorder, Therapeutic Intervention, Psychopathy in Youth.

INTRODUCTION

Incarceration of youth offenders within the justice system results in a higher risk of lifetime consequences, such as more persistent and learned antisocial behaviors. A recent study by Robinson et al. (2020) revealed that 25-30% of adolescents with conduct problems possess Callous Unemotional (CU) traits that are implicated in the severe and violent offending patterns of behavior. CU traits are characterized by aggressive behavior, a lack of guilt or empathy, and a deficiency in emotionality, specifically with processing negative emotions [1]. Additionally, one in seven adolescent offenders scored significantly high on CU traits according to the Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits (ICU) [2]. This is important to consider within this population of incarcerated youths because these traits can lead to more persistent antisocial behavior (Robinson et al., 2020), more repeated offending [3], and less responsiveness to traditional clinical intervention and treatment [4]. However, there seems to be a gap in the literature on the intervention methods that effectively reduce the effects of CU traits on offending behavior, which warrants further research. Thus, in this review I aim to conduct a systematic, guided investigation of the effects of CU traits on youth delinquency because of the important role that incarceration plays in increasing antisocial behaviors in order to recognize risk and protective factors that may help develop foundations for successful and comprehensive treatment methods. Furthermore, this review primarily focuses on a population of adolescent male youths in contact with the juvenile justice system that are specifically between the ages of 13-17 years old. This population was chosen because high CU traits are more prevalent in boys than in girls will be reviewed in this study will measure the trajectory of offending behavior after first arrests, while identifying the role that CU plays in this relationship. Primarily, this is chosen in order to recognize the particular effects that incarceration has on high-CU youths.

Variants of Callous Unemotional Traits

In order to differentiate between the types of antisocial behavior youths with CU traits are involved in, it is necessary to understand the different variants of CU traits. The construct of Callous Unemotionality in children and adolescents has been identified to arise from two different etiological pathways, one for primary variants and the other for secondary variants. According to Craig, Goulter, and Moretti [5], individuals with primary variants of CU traits are characterized by more deficits in emotion processing and a diminished sensitivity to others’ emotional cues as a result of temperamental and genetic-based adaptations. On the other hand, secondary variants are characterized by affective disturbances as a result of trauma, chronic maltreatment, and other adverse socio-environmental factors that result in higher levels of anxiety compared to primary variants. These are important to consider because these differing etiological pathways lead to particular antisocial behaviors. In fact, youth with secondary variants of CU traits exhibit more variability in their violent behavior in comparison with those with the primary variant. Secondary variants also display higher levels of reactive aggression, but similar levels of proactive aggression to those with the primary variant [5]. This suggests that individuals with different variants of CU traits might need different kinds of intervention methods that are tailored to their specific level and type of CU, especially if they have had contact with the criminal justice system. In a study by Robertson, Ray, Frick, and Thornton [6], 92% of individuals with high levels of the secondary variant of CU with high anxiety committed at least one violent act while institutionalized over 2 years. Further, CU traits were found to significantly increase the likelihood of being arrested for any violent offense. Thus, this already high rate of crime tied with the high rates of incarceration exemplifies the necessity for these particular individuals to avoid additional contact with the justice-system and instead seek treatment for reasons that will be explored further below.

METHODS

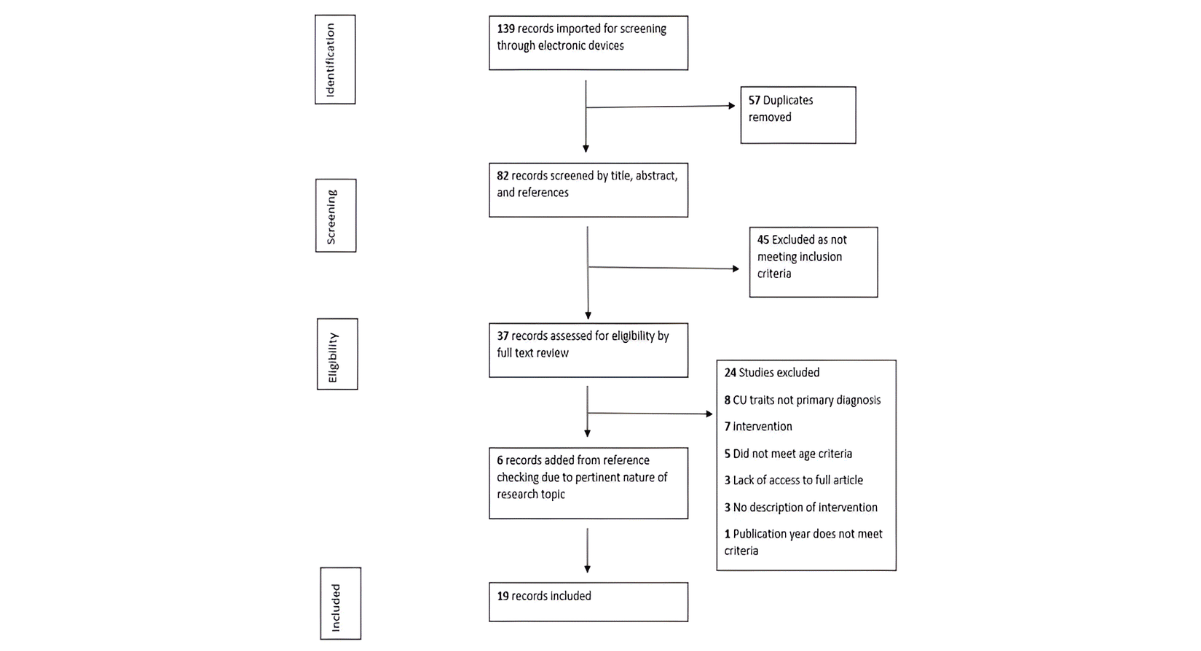

The current paper investigates the effects of involvement in the criminal justice system on youth offenders high on callous unemotional traits. Two databases, Google Scholar and APA PsychNet, were used to search for empirical, peer reviewed research published within the last 20 years. To identify studies investigating CU traits, clinical intervention, and justice-involved youth, the following key terms were used to search the previously stated databases: “Callous Unemotional traits,” “Youth delinquency,” “Anti-social behavior,” “Treatment Outcomes,” “Adolescent Offenders,” and “Conduct Disorder.” Titles and abstracts were screened based on the aims of this research. No additional criteria were specified based on study design except for publications restricted to peer-reviewed scholarly articles that are written in or translated to the English language. Additionally, past research has consistently used the 24-item scale Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits (ICU) to measure three specific psychometric factors of CU traits, which are Callousness, Uncaringness, and Unemotionality [7]. These three factors are highly relevant when investigating the role of CU traits on youth offending behavior because they identify key aspects of Callous Unemotionality that are associated with antisociality, such as aggression reactivity for example [3]. A thorough review of all references was also included in order to retrieve theoretically-relevant articles, which is shown in figure 1. Based on this method, a total of 19 studies were retained.

Figure 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria of systematic review process. Review of Literature

Individual Dispositional Effects of CU Traits

The main focus of the literature on CU traits and the population of youth offenders focused primarily on individual factors. First, Kimonis, Graham, and Cauffman [7] aimed at investigating the interaction between CU traits and deficits to attention when focusing on distressing stimuli. Specifically, they hypothesized that CU traits would interact with aggression. The CU traits that were measured are the foundational three-factors of the ICU, which are Callousness, Uncaringness, and Unemotionality. In addition, the authors’ second aim was to test if these effects would be the same in a subsample of Latino and Black incarcerated boys. The main findings that Kimonis et al. identified were that male youth offenders that scored high on uncaringness in CU traits were less attentionally engaged by distress cues and reflected more proactive aggression. This is highly important because of the fact that the criminal justice system is based on retributive methods of correcting behavior [8]. Since youths high on CU traits are insensitive to distressing cues, the effect of punishment may no longer hold effectively as it is not attentionally engaged with by individuals who are high on CU traits and will in turn increase their involvement with proactive aggression over time. Additionally, this study revealed emotional deficits in Black youth that differed from Latinos. This demonstrates that there appears to be a racial difference in emotional processing within this population of high CU individuals that may be a result of cultural norms within one’s ethnic group. Thus, identifying dispositional effects of CU on youth involved with the justice system is necessary to further understand the relationship between incarceration and youths with high CU traits. Consequently, it is critical to recognize how proactive aggression resulting from CU traits is associated with emotional deficits, which may stem from exposure to violence and trauma. According to [3], higher levels of CU traits exacerbated the effect of angry rejection sensitivity that facilitates aggressive behavior when adolescents anticipate or experience rejection. This relationship appears to be moderated by trauma Importantly, it is worth noting that adolescents who are in contact with the criminal justice system are exposed to an increasingly violent environment, which may elevate their levels of trauma. This has detrimental effects on individuals with high CU traits because the effects of anger rejection sensitivity in trauma exposed individuals were highly associated with recidivism in youths with high CU traits. So, not only are these individuals in trauma-filled environments more sensitive to reacting aggressively, but they are also experiencing more trauma as a result of their frequent exposure to violence, which could then exacerbate their already existing mental health issues [3 - 9]. Thus, this relationship between CU traits and youth delinquency depicts vital considerations for the rates of crime and recidivism of antisocial behavior, which can enlighten future treatment methods. In fact, Simmons et al. [10] focused on a sample of 1,216 adolescent boys who were incarcerated for the first time within the justice system with the aim of examining the interactive effects between CU traits, psychosocial maturation (PSM), and offending behavior. The sample methods identified in 2018 demonstrate an increase in validity compared with prior research. First, the sample size is larger, having more statistical power for future generalizations of results. Second, the study measured this relationship for a year after first arrest depicting more longitudinal data compared with the two studies discussed above. Additionally, participants were between the ages of 13 and 17 years old and were assessed for CU traits through the ICU and PSM through the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory. The Weinberger Adjustment Inventory analyzes measures of impulse control, suppression of aggression, and consideration of others – which are subscales of PSM in adolescents. A reoffending variety score was calculated using the Self-Report of Offending scale to assess the variety of offenses committed in the following year. Statistically, a Pearson’s zero-order correlation was used to examine these associations between the main variables and a negative binomial regression model was conducted to analyze whether PSM and CU were associated for youth offending when accounting for age, IQ, parental education, race, and baseline self-reporting. Using this longitudinal data, the authors demonstrated that youths high in CU traits engaged in higher rates of offending following their first arrest. This signifies the role that incarceration has on youths who score high in CU traits, as involvement with the criminal justice system resulted in increases in antisocial behavior. However, psychosocial maturation was associated with less offending in low-CU youths, but not in high-CU youths. This provides evidence that psychosocial maturation over adolescence and adulthood significantly varies from normative experiences in youth with high CU traits compared to low-CU youths. These findings further emphasize the need for tailored treatments for high-CU youths in order to replace the current retributive methods of the criminal justice system.

Limitations of Retributive Systems for High-CU Youths

The criminal justice system in the US relies on three branches in order to enforce legal standards. These are the police, the courts, and the corrections/incarceration system. However, this correctional system has shifted from initially focusing on rehabilitation to now adopting retributive justice values Hermann, 2017 [8]. These values are based on the notion that when an offender commits a crime, they must be punished in proportion to the level of offense committed. Notably though, most juvenile delinquent behavior is consistent with a typical trend in adolescence marked by exploration and offending patterns that in most cases are purely age-related [11]. Therefore, it seems implausible and counterproductive that the corrections system uses these retributive methods to correct typical adolescent behavior. In fact, exposure to the criminal justice system and specifically being incarcerated has been shown to generally cause more harm by increasing rates of recidivism after first offense. This is most likely due to the school of crime and high stress environment that these offenders are being exposed to within the incarceration system. Moreover, juvenile delinquency puts a large economic burden on the criminal justice system, especially given the increasing rates of recidivism [12]. This is unfortunate, since retribution does not seem to be an efficient way of targeting delinquency in general. As it happens, money can be better spent on treatments that target the root of delinquent behavior in crime-persistent youth, which in turn leads to more productive change in antisocial behavior and will be further discussed in this review. Additionally, this persistence in crime for youth is exacerbated by the presence of CU traits. This is because of the characteristics of CU traits, which are marked by higher levels of antisocial and delinquent behavior, that stem from their uncaring and callous nature. So, in line with the hypothesis, youths with CU traits must then experience more negative consequences as a result of being associated with the criminal justice system, which seems to aggravate delinquent behavior.

Consequences of Criminal Justice System Involvement in Youths with CU Traits

Once individual effects of CU traits were well established, research began to investigate contextual effects of CU Traits. Specifically, literature explored the impact of the criminal justice system on youth offenders with high levels of CU. Ray et al. 2019 researched the developmental trajectory of CU traits in 1,120 justice-involved boys aged 13-20 years old over 3 years. The large sample size and longitudinal design demonstrates strong validity in psychological research.

Neighborhood Disorganization and Peer Influence

CU traits were consistently assessed every 6 months for 36 months through the ICU. While the main focus of this study was to investigate external impacts on CU, individual factors including impulse control, delinquency, ethnicity, and intelligence were also assessed. Measures of non-justice contextual factors included maternal warmth, delinquent peer association, neighborhood disorder, and exposure to violence. In addition, youth with high levels of CU and more contact with the justice system show moderate stability of these traits over time that desist much later into adulthood when compared with low-CU individuals, signifying once again a non-normative developmental trend among these individuals. Racial differences were observed, with White offenders showing higher baseline levels of CU traits compared to Black offenders. However, White offenders demonstrated a larger decline in CU traits over three years compared with Black offenders. Furthermore, this study also provided empirical evidence that self-reported delinquency, neighborhood disorganization, and deviant peers are positively associated with CU traits. On the other hand, impulse control and maternal warmth were negatively associated with CU traits, indicating that these factors act as a protective factor for CU trait development.

Maternal Warmth and Family-Level Protective Factors

Understanding the longitudinal development of CU traits, as well as protective and risk factors for this development, is important for developing effective intervention methods for treatment in order to avoid the detrimental effects that interaction with the criminal justice system can do for youths high on CU traits. Subsequently, the literature expanded on the institutional involvement of youth offenders high in CU traits. Robertson et al. investigated how CU traits moderate the effect of justice system involvement on delinquency and antisocial behavior. Following a similar trend to past literature on CU traits, higher levels of CU traits are associated with slower desists from crime. These results indicate that higher levels of involvement with the justice system are a risk factor for antisocial behavior and increased reoffending rates. Specifically, youths who are high on CU traits and exhibit psychopathic tendencies, such as lack of empathy and low fearfulness-response, compared with those who are not high on CU are especially at risk for involvement with the criminal justice system. High CU youth offenders - both male and female - who had major traits of CU exhibited high rates of overall aggression, proactive aggression, and violent delinquency that were elevated from those with lower or no CU traits Thus, it seems evident that youth offenders who are high on CU traits and are involved with the criminal justice system experience consequences unlike those who do not have these traits. This detrimental relationship that CU individuals have with the justice system may be explained by several factors, one of which may be the association with other peer delinquents in such a violent environment. A different study conducted by Robertson et al. aimed at investigating the role of CU after first arrest at predicting gun carrying and use in justice system-involved youths and gun carrying in their peers. Participants of this study included 1,215 male offenders between the ages of 13-17 who were arrested for the first time. The sample of youths were assessed at baseline within 6 weeks of their first arrest, every 6 months for 36 months after first arrest, and then again at 48 months post first arrest. Main variables of the study consisted of CU measured through the ICU, peer gun ownership and carrying assessed by the Association with Deviant Peers Scale, and personal gun carrying and use through self-reports. Additionally, the demographic control variables included age, race/ethnicity, intelligence, and impulse control. Accordingly, the regression analyses signified that CU traits increased the frequency of personal gun carrying and use, even when accounting for risk factors of gun use and CU. Also, CU traits moderated the relationship with gun carrying in peers and became a risk factor for recidivism, violence, and severe delinquency. There are many negative consequences associated with these findings. Among them, high-CU youths indicate strong influences of violence and antisocial behaviors in their peers, which will in turn increase the overall rate of crime among adolescents. Given the past research on the influence of peer delinquency on offending behavior, it seems evident that low-CU individuals will be more likely to be severely involved with violence as a result of the association with high-CU individuals and crime.

Therapeutic Alliance and Clinical Intervention Strategies

The importance of this research topic relies on the empirical evidence that youth offenders who are high on CU traits do not benefit from traditional treatment - especially incarceration - and may instead require tailored intervention methods to help reduce the severe rates of delinquency, recidivism, and antisocial behavior observed amongst this population [13]. So, by reviewing past literature to determine an overall trend in CU research on youth offending behaviors, it seems indisputable that higher rates of severe delinquency, recidivism, and antisocial behaviors are associated with higher levels of CU traits. However, as mentioned in previous sections, important risk and protective factors have been identified to play a moderating role in this relationship. First, risk factors include greater involvement with the justice system, self-reported delinquency & neighborhood disorder, deviant peers, and negative future outlooks on prosocial outcomes. Most of these factors have been associated with increased involvement with the justice system as it exposes an individual to deviant peers, reduces future outlooks on success and prosocial outcomes, and exposes these adolescents to violent environments as outlined above in this review. Thus, minimizing contact with the criminal justice system for youth delinquents seems to be imperative for better treatment outcomes. Additionally, protective factors for youths high in CU traits include impulse control & maternal warmth, psychosocial maturation in low-CU individuals & higher rates of motivation for, and higher levels of trust within the therapeutic-alliance relationship. These factors are also incredibly important to consider overall because they provide insight into future directions of clinical treatment and on ways of developing effective tailored methods that target these protective factors and aim to reduce the overwhelming risk of CU on youth delinquency.

Future Orientation, Self-Esteem, and Motivation

Finally, the relationship among CU traits and future orientation in youth offenders was investigated by Walker et al. to orient clinicians on how adolescents with CU traits view themselves and potential future successes. Future orientation can be defined as, “an element of identity formation that is conceptualized as one’s cognitions and perceptions of the future, such as thoughts, plans, motivations, hopes, and feelings”. This is important because positive future orientation has been linked with reducing future delinquent behaviors [14]. So, Walker et al hypothesized that negative perceptions of future success will in turn lead to less prosocial behavior. The participants of this study were 1,216 male youth offenders from the Crossroads study who were recruited to the sample after their first arrest. The ages of these individuals were between 13-17 years old with 45.9% identifying as Latino, 36.9% identifying as Black, and 14.7% identifying as White. Particularly, self-reported offending was assessed through the Self-Report of Offenses Inventory (SRO), CU traits were measured by the ICU, and self-esteem was measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale, while controlling for age, IQ, and ethnicity. In testing for the hypothesis, the results indicate that CU traits were negatively associated with all the measures of future orientation, self-esteem, optimism, and self-reported delinquency at both high and low measures of self-esteem. Consequently, this plays a role in the efficiency of treatment on individuals with CU because without future orientation there is nothing positive to expect out of clinical intervention methods. Thus, it is absolutely necessary to consider these cumulative factors to develop efficient tailored intervention methods to treat youths with high CU traits.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Findings and Implications for Intervention This review aimed at investigating the effects of Callous Unemotional (CU) traits on youth delinquents involved with the justice system. According to the literature, it seems evident that involvement with the justice system is not an effective rehabilitation strategy for youth high on CU traits and can actually exacerbate problematic behaviors. Particularly, incarceration for individuals with high CU traits tends to lead to more persistent antisocial behavior [15 - 16], more repeated offending, and less responsiveness to treatment. Past research has indicated that this is because youths who are high on CU traits tend be extremely impulsive and resistant to punishment [17]. Currently, the criminal justice system approaches rehabilitating delinquents for antisocial behavior through the retributive process of incarceration. However, as indicated throughout the literature, adolescents with high CU traits do not respond well to retributive processes as they are insensitive to distressing cues or punishment. Additionally, involvement with the criminal justice system exposes these high risk individuals to other delinquent peers, which in turn can only strengthen their relationship with antisociality and crime. Thus, it is evident within the review of the literature that juvenile offenders with high CU traits do not respond well to retributive measures, specifically in today’s way of incarceration. Instead, it seems that tailored interventions based on unique behavioral and emotional characteristics are more successful at alleviating the effects of CU traits. This is highlighted by emerging evidence of the importance of contextual factors in moderating the relationship between delinquency and CU traits. Furthermore, peer delinquency, neighborhood disorder, involvement in the criminal justice system, and a diminished future orientation are important risk factors that tend to exacerbate antisocial tendencies in youth with high-CU traits. On the other hand, therapeutic alliances, maternal warmth, impulse control, and psychosocial maturation function as protective factors and allow for development of more successful clinical intervention methods. These results highlight the necessity of systemic change and the application of developmentally appropriate, empirically supported treatment approaches. So, some recommendations for rehabilitating and supporting youths high on CU traits involve tailored interventions. These methods demand individualizing comprehensive interventions that address the unique requirements specific to the adolescent offender that are reinforced by empirical research. The most supported intervention method for youths high on CU traits is reward-based strategies [18]. This is because, as mentioned previously, youths who are high on CU traits have attentional deficits that neglect distressing cues and in turn promote high drive and low fearfulness characteristics that make punishments less effective as a correction strategy [19]. However, reward-based interventions focus on positive reinforcement to induce prosocial behaviors and tend to be more effective since they target the self-interests of these youths - especially when this intervention is paired with the promotion of warmth in parent-child relationships. This promotion of warmth can be fostered during parent-child interaction therapy and through psychoeducative methods. Noticeably, however, parent-training interventions tend to produce the most positive change in CU traits and antisocial behavior when delivered at an early age. A potential explanation for this finding could be that the child’s understanding of relationships and societal expectations would still be developing and thus these interventions could potentiate more empathy and prosocial behaviors at a more sensitive age for retention. Despite the relevance of these studies on youth offending behavior and CU, it is important to acknowledge limitations. So, the initial limitations identified with the earlier studies on this topic include concerns with external validity because of the smaller sample size and limited time-frame analysis. On the other hand, it is important to note that the development of research since 2017 has improved in these methods as demonstrated in the most current literature. Furthermore, the majority of the studies reviewed in this paper are correlational thereby limiting the internal validity of the overall study’s ability to identify a cause-and-effect relationship between CU traits and involvement with the criminal justice system for youth offending. However, this correlational form of analysis was chosen because of the unethical nature associated with grouping CU traits and delinquents as independent variables, given that it could only add more stigma to that individual. Most importantly, past research which focused on dispositional factors alone failed to account for the strong situational factors that in turn can lead to the creation of treatment methods tailored to an adolescent’s level of risk.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, incarceration for individuals with high CU traits tends to lead to more persistent antisocial behavior, more repeated offending, and less responsiveness to treatment. For this reason, it is necessary for future researchers to focus on risk and protective factors that are associated with CU traits and youth offending behavior. This is the case because of the detrimental effects that involvement with the criminal justice system has on youth high on CU traits. Therefore, establishing successful clinical treatments that are founded upon the protective factors mentioned in this review has provided some practical implications of the literature on treatment for callous unemotional traits and youth offending behavior that will hopefully replace the retributive justice system as a rehabilitative method.

REFERENCES

- Kimonis ER, Frick PJ, Skeem JL, Marsee MA, Cruise K, Munoz LC, Aucoin KJ, Morris AS. Assessing callous–unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits. International journal of law and psychiatry. 2008 ;31(3):241-52. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Kimonis ER, Fanti K, Goldweber A, Marsee MA, Frick PJ, Cauffman E. Callous-unemotional traits in incarcerated adolescents. Psychological assessment. 2014 ;26(1):227. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Mozley MM, Modrowski CA, Kerig PK. The roles of trauma exposure, rejection sensitivity, and callous‐unemotional traits in the aggressive behavior of justice‐involved youth: A moderated mediation model. Aggressive behavior. 2018 ;44(3):268-75. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Mattos LA, Schmidt AT, Henderson CE, Hogue A. Therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in the outpatient treatment of urban adolescents: The role of callous–unemotional traits. Psychotherapy. 2017 ;54(2):136. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Craig SG, Goulter N, Moretti MM. A systematic review of primary and secondary callous-unemotional traits and psychopathy variants in youth. Clinical child and family psychology review. 2021 ;24(1):65-91. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Robertson EL, Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Wall Myers TD, Steinberg L, Cauffman E. The associations among callous-unemotional traits, worry, and aggression in justice-involved adolescent boys. Clinical Psychological Science. 2018 ;6(5):671-84. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor]

- Kimonis ER, Graham N, Cauffman E. Aggressive male juvenile offenders with callous-unemotional traits show aberrant attentional orienting to distress cues. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2018 ;46(3):519-27. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Hermann DH. Restorative justice and retributive justice: An opportunity for cooperation or an occasion for conflict in the search for justice. Seattle J. Soc. Just.. 2017;16:71. [Google Scholor]

- Ray JV, Frick PJ, Thornton LC, Wall Myers TD, Steinberg L, Cauffman E. Estimating and predicting the course of callous-unemotional traits in first-time adolescent offenders. Developmental psychology. 2019 ;55(8):1709. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Simmons C, Fine A, Knowles A, Frick PJ, Steinberg L, Cauffman E. The relation between callous‐unemotional traits, psychosocial maturity, and delinquent behavior among justice‐involved youth. Child development. 2020 ;91(1):e120-33. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Pechorro P, Braga T, Ray JV, Gonçalves RA, Andershed H. Do incarcerated male juvenile recidivists differ from first-time offenders on self-reported psychopathic traits? A retrospective study. European journal of criminology. 2019 ;16(4):413-31. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor]

- White SF, Frick PJ, Lawing K, Bauer D. Callous–unemotional traits and response to Functional Family Therapy in adolescent offenders. Behavioral sciences & the law. 2013 ;31(2):271-85. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Walker TM, Robertson EL, Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Myers TD, Steinberg L, Cauffman E. Relationships among callous-unemotional traits, future orientation, optimism, and self-esteem in justice-involved adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2020 ;29(9):2434-42. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor]

- Prince DM, Epstein M, Nurius PS, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB. Reciprocal effects of positive future expectations, threats to safety, and risk behavior across adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2019 ;48(1):54-67. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Robertson EL, Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Wall Myers TD, Steinberg L, Cauffman E. Do callous–unemotional traits moderate the effects of the juvenile justice system on later offending behavior?. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2021 ;62(2):212-22. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Robertson EL, Frick PJ, Walker TM, Kemp EC, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Wall Myers TD, Steinberg L, Cauffman E. Callous-unemotional traits and risk of gun carrying and use during crime. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2020 ;177(9):827-3 3. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Hawes DJ, Dadds MR. The treatment of conduct problems in children with callous-unemotional traits. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2005 ;73(4):737. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Kimonis ER, Fanti KA, Isoma Z, Donoghue K. Maltreatment profiles among incarcerated boys with callous-unemotional traits. Child maltreatment. 2013 ;18(2):108-21. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

- Hawes DJ, Price MJ, Dadds MR. Callous-unemotional traits and the treatment of conduct problems in childhood and adolescence: A comprehensive review. Clinical child and family psychology review. 2014 ;17(3):248-67. [CrossRef] [Google Scholor] [PubMed]

Indexed In

DOAJ

CrossRef

PubMed

MEDLINE

ResearchBib

OAJI

Sindexs

EBSCO A-Z / Host

OCLC - WorldCat

Journal Flyer