ABSTRACT

The global transition to renewable energy has elevated solar power as a key driver of sustainability, yet its intermittent nature and integration challenges demand advanced solutions to optimize efficiency and reliability. This research investigates the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in revolutionizing solar energy management, focusing on machine learning and optimization techniques to enhance system performance, the experiment was calibrated in MATLAB environment. We evaluate algorithms including Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Linear Regression (LR), and Genetic Algorithms (GAs), applied to solar power forecasting and parameter optimization. Our methodology employs SVR with an RBF kernel and grid search, achieving precise predictions of solar power output with reduced forecasting errors, while GAs optimizes system parameters to a fitness value of 23.20 kWh, even under constraints like a 90° panel tilt. Comparative analysis reveals SVR and GA outperform ANNs and LR, demonstrating their adaptability to weather fluctuations. This study highlights AI’s transformative impact on solar energy efficiency and sustainability, offering valuable implications for researchers and industry stakeholders.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence; Solar Energy Management; Optimization Algorithms; Forecasting Efficiency; Photovoltaic Systems

INTRODUCTION

Amid escalating environmental concerns and the imperative for sustainable development, the energy sector stands as one of the primary domains undergoing profound transformation. Artificial intelligence has emerged as a pivotal force in reshaping decision-making processes within sustainable energy management through the advancement of sophisticated technologies. Global energy consumption has risen sharply throughout the twenty-first century, necessitating a fundamental paradigm shift toward environmentally compatible and sustainable alternatives. As conventional energy resources become depleted and anxieties surrounding climate change intensify, the pursuit of effective, eco-friendly, and sustainable energy management has assumed unprecedented importance. Traditional approaches to energy planning and distribution prove inadequate in addressing the complex challenges posed by climate variability, resource limitations, and increasing demand [1]. Consequently, the adoption of artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative strategy for reshaping decision-making processes and enhancing the sustainability, resilience, and efficiency of energy systems. The evolution of sustainable energy practices underscores pivotal milestones and challenges that continue to shape the contemporary energy sector. This historical perspective emphasizes the critical imperative for innovative decision-making approaches. Furthermore, it facilitates a comprehensive examination of the seamless integration of AI technologies within frameworks for sustainable energy management [2-3]. This study investigates the intricate interplay between artificial intelligence and decision-making frameworks within the domain of sustainable energy management, situated amid the confluence of pressing environmental necessities and rapid technological advancements.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a significant instrument for enhancing the performance and operational efficiency of renewable energy systems and intelligent power grids. Advanced AI methodologies, such as machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and neural networks (NN), are increasingly utilized across multiple dimensions of solar energy production and grid management. These approaches facilitate greater precision in solar irradiance forecasting, more reliable predictions of power generation, and optimized strategies for energy storage and distribution. Within solar energy infrastructures, AI-based algorithms are deployed for maximum power point tracking, predictive maintenance, and fault detection [4-5]. Machine learning models are capable of examining historical datasets and meteorological patterns to predict solar energy production, thereby facilitating improved integration and management within electrical grids. Advanced DL methods are applied in image recognition tasks for the inspection of photovoltaic panels and the enhancement of their operational performance. In the context of smart grids, artificial intelligence assumes a pivotal role in demand-side management, load prediction, and the maintenance of grid stability. Energy management systems powered by artificial intelligence optimize the equilibrium between supply and demand, thereby minimizing energy wastage and enhancing overall system efficiency. Furthermore, artificial intelligence algorithms are deployed in cybersecurity protocols to safeguard smart grid infrastructure against potential threats and vulnerabilities [6]. The incorporation of artificial intelligence into renewable energy systems and smart grids constitutes a comprehensive strategy for improving energy efficiency. Through the application of advanced data analytics and intelligent decision-making processes, AI technologies facilitate the optimal exploitation of renewable resources, enhance grid stability and reliability, and mitigate adverse environmental effects [7-8]. With ongoing advancements in research, the integration of artificial intelligence, solar power technologies, and intelligent grid systems offers considerable potential for achieving a more sustainable and efficient energy landscape.

The rapid growth of solar energy deployment worldwide has brought to the forefront a series of complex challenges that threaten to impede the sector's continued expansion and efficiency. These challenges, ranging from technical hurdles to economic constraints, underscore the urgent need for innovative management solutions. The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in solar energy management presents a promising avenue for addressing these issues, yet its implementation is not without its own set of problems and limitations. One of the primary challenges in solar energy management is the inherent variability and intermittency of solar resources. Unlike conventional power sources, solar energy production is highly dependent on weather conditions, which can change rapidly and unpredictably. This variability poses significant challenges for grid operators, who must maintain a delicate balance between supply and demand to ensure grid stability [9]. Traditional forecasting methods often fall short in accurately predicting solar irradiance and energy output, leading to suboptimal utilization of solar resources and increased reliance on backup power sources. As solar installations grow in scale and complexity, the task of monitoring and maintaining these systems becomes increasingly daunting. Large solar farms can consist of thousands of individual panels spread across vast areas, making it challenging to detect and respond to performance issues in a timely manner. Inefficiencies in maintenance practices can lead to reduced energy output, increased downtime, and higher operational costs, ultimately impacting the economic viability of solar projects [10].

The integration of solar energy into existing power grids presents another set of challenges. The variable nature of solar power can cause voltage fluctuations and frequency instabilities in the grid, particularly in regions with high solar penetration. Traditional grid management systems are often ill-equipped to handle the complexities introduced by large-scale solar integration, leading to curtailment of solar energy during peak production periods and inefficient utilization of available resources [11]. While AI presents potential solutions to many of these challenges, its application in solar energy management is not without its own set of problems. One significant issue is the quality and availability of data required to train AI models effectively. Solar energy systems generate vast amounts of data, but this data is often fragmented, inconsistent, or incomplete. Ensuring data quality and developing robust data management practices are crucial challenges that need to be addressed to fully leverage the potential of AI in this domain. Another problem lies in the interpretability and transparency of AI algorithms. Many advanced AI techniques, such as DL, operate as "black boxes," making it difficult to understand and validate their decision-making processes. This lack of transparency can lead to skepticism and resistance from stakeholders in the solar energy industry, particularly when it comes to critical decisions affecting system performance and grid stability [12-13] . The implementation of AI systems in solar energy management also faces economic barriers. The development and deployment of AI solutions require significant upfront investments in technology, infrastructure, and expertise. For many solar energy operators, particularly smaller-scale installations, these costs can be prohibitive, potentially exacerbating inequalities in the sector and limiting the widespread adoption of AI-driven management solutions [14].

The investigation into the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in solar energy management holds profound significance across multiple dimensions. The spread encompasses technological advancement, economic implications, environmental sustainability, and energy policy. This study's outcomes have the potential to inform and influence various stakeholders in the energy sector, from solar farm operators and grid managers to policymakers and researchers. From a technological perspective, this research contributes to the growing body of knowledge at the intersection of AI and renewable energy. By exploring the capabilities and limitations of AI in addressing the unique challenges of solar energy management, the study paves the way for more targeted and effective development of AI solutions in this domain. The findings can guide future research and development efforts, potentially leading to breakthroughs in areas such as solar forecasting, predictive maintenance, and grid integration [15].

The economic implications of this study are substantial. As the global solar energy market continues to expand, the need for cost-effective and efficient management solutions becomes increasingly critical. The insights gained from this research can inform investment decisions in AI technologies for solar energy management, helping operators to optimize their resources and maximize returns on investment. Moreover, by highlighting the potential of AI to enhance the efficiency and reliability of solar energy systems, this study could contribute to making solar power more competitive with traditional energy sources, thereby accelerating its adoption [16-17]. From an environmental standpoint, the significance of this research cannot be overstated. As the world grapples with the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and combat climate change, maximizing the efficiency and reliability of renewable energy sources is paramount. By exploring how AI can optimize solar energy production and integration, this study contributes to broader efforts to decarbonize the global energy system. The potential for AI to enhance the performance of solar installations could lead to increased renewable energy generation, reduced reliance on fossil fuels, and consequently, lower carbon emissions [18].

For the scientific community, this study contributes to bridging the gap between AI research and solar energy engineering. By providing a comprehensive analysis of the current state of AI applications in solar energy management, as well as identifying areas for future research, the study serves as a valuable resource for researchers in both fields. It may inspire new collaborations and interdisciplinary approaches to solving complex challenges in renewable energy management [19]. From a technological perspective, the study can guide future research and development efforts, potentially leading to breakthroughs in areas such as solar forecasting, predictive maintenance, and grid integration. The economic implications of this study are substantial, as the need for cost-effective and efficient management solutions becomes increasingly critical. such that the insights gained from this research can inform investment decisions in AI technologies for solar energy management. From an environmental standpoint, the potential for AI to enhance the performance of solar installations could lead to increased renewable energy generation, reduced reliance on fossil fuels, and consequently, lower carbon emissions. In terms of energy policy and governance, AI systems take on more critical roles in energy management, questions of regulation, standardization, and ethics come to the fore. The study can as well guide policy decisions on research funding, incentives for AI adoption in the energy sector, and strategies for workforce development to address the skills gap in this interdisciplinary field. This study's outcomes have the potential to inform and influence various stakeholders in the energy sector, from solar farm operators and grid managers to policymakers and researchers. For the scientific community, it contributes to bridging the gap between AI research and solar energy engineering. By providing a comprehensive analysis of the current state of AI applications in solar energy management, as well as identifying areas for future research, the study serves as a valuable resource for researchers in both fields. It may inspire new collaborations and interdisciplinary approaches to solving complex challenges in renewable energy management. The objectives of this study are as follows:

- To evaluate the impact of advanced AI algorithms on solar energy output and system efficiency, compared to simpler algorithms, while controlling for weather conditions and system design parameters.

- To examine the influence of variable weather conditions on the effectiveness of AI algorithms in enhancing solar energy output and efficiency, irrespective of the type of AI algorithm used.

- To investigate how AI algorithms optimize solar energy output and efficiency in complex system designs (e.g., multi-orientation arrays, diverse panel types) compared to simpler system designs, while controlling for weather conditions

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review, relevant studies, and foundational work. Section 3 outlines the methodology and the details of the approaches used in the proposed system. Section 4 presents the results and discussion, and analyzes the study’s findings and their implications. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study and highlights potential directions for future research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Conceptual Review

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in solar energy management represents a significant leap forward in renewable energy technology. This chapter provides a comprehensive review of the literature surrounding this rapidly evolving field. The review begins with an exploration of key conceptual explanations, including the challenges posed by solar energy variability, the role of smart grid integration, the power of AI-driven predictive analytics, system optimization techniques, the broader context of AI in energy systems, the impact of weather conditions on solar power generation, and the importance of system design parameters. Following this, the theoretical framework underpinning the application of AI in solar energy management is examined through the lenses of Systems framework, ML models, and optimization algorithms. The chapter concludes with an empirical review of recent studies that have applied these concepts and theories in practical settings. This comprehensive approach provides a solid foundation for understanding the current state of AI applications in solar energy management and identifies promising areas for future research and development [20].

Solar Energy Variability and Intermittency

The inherent variability and intermittency of solar energy pose significant challenges to its widespread adoption and efficient integration into existing power grids. Solar power generation is heavily dependent on weather conditions, time of day, and seasonal variations, leading to fluctuations in energy output that can be difficult to predict and manage [20-21]. This variability is a fundamental characteristic of solar energy systems and has far-reaching implications for energy management, grid stability, and the overall reliability of solar power as a primary energy source. One of the primary challenges associated with solar energy variability is the mismatch between peak energy production and peak demand. Solar panels typically generate the most electricity during midday when sunlight is most intense, but this often does not align with periods of highest energy consumption, which typically occur in the early morning and evening [22]. This misalignment necessitates effective energy storage solutions and sophisticated management systems to balance supply and demand.

The intermittent nature of solar energy also introduces complexities in grid management. Sudden changes in cloud cover, for instance, can lead to rapid fluctuations in power output, potentially causing voltage and frequency instabilities in the grid [23]. These fluctuations can be particularly problematic in areas with high solar penetration, where the grid must be capable of quickly ramping up or down alternative power sources to maintain stability. Furthermore, seasonal variations in solar irradiance can lead to significant differences in energy production throughout the year. In many regions, solar energy output is substantially lower during winter months due to shorter days and less direct sunlight, creating challenges for long-term energy planning and reliability [24].

The variability and intermittency of solar energy also have economic implications. The need for backup power sources or energy storage systems to compensate for periods of low solar production can increase the overall cost of solar energy integration. Additionally, the uncertainty in power output can complicate energy market operations and pricing mechanisms [25]. Addressing these challenges requires innovative approaches to solar energy management. Advanced forecasting techniques, improved energy storage technologies, and smart grid systems are all crucial components in mitigating the effects of solar energy variability and intermittency. The application of AI in this context offers promising solutions, enabling more accurate predictions of solar output, optimized energy storage management, and intelligent load balancing across the grid.

The integration of solar energy into smart grids represents a critical advancement in renewable energy management, offering solutions to many of the challenges posed by solar variability and intermittency. Smart grids, characterized by their use of digital communication technologies to detect and react to local changes in usage, provide a flexible and responsive infrastructure capable of efficiently managing the dynamic nature of solar energy [26]. At the core of smart grid integration is the concept of bi-directional communication between various components of the power system. This allows for real-time monitoring and control of energy flow, enabling grid operators to balance supply and demand more effectively. In the context of solar energy, this means that fluctuations in solar power output can be quickly detected and compensated for, either through the activation of alternative energy sources or by adjusting demand through load management techniques [27-28].

One of the key features of smart grid integration for solar energy is the ability to implement advanced demand response programs. These programs incentivize consumers to adjust their energy usage based on the availability of solar power, helping to align demand with periods of peak solar production. For instance, smart appliances can be programmed to operate during times of high solar output, maximizing the use of clean energy and reducing strain on the grid during peak demand periods [19-28]. Smart grids also facilitate the integration of energy storage systems, which are crucial for managing the intermittency of solar power. By intelligently controlling when to store excess solar energy and when to release it back into the grid, smart grids can help smooth out the variability in solar power production. This not only improves the reliability of solar energy but also enhances the overall stability of the power system [29,24]. Furthermore, smart grid technologies enable more efficient management of distributed solar resources. With the increasing adoption of rooftop solar panels, power systems are becoming more decentralized. Smart grids can effectively coordinate these distributed resources, treating them as a virtual power plant that can be managed collectively to support grid operations [30].

Smart Grid Integration

The integration of solar energy into smart grids also opens up new possibilities for market participation. Through advanced metering and communication systems, prosumers (consumers who also produce energy) can actively participate in energy markets, selling excess solar power back to the grid or to other consumers. This creates a more dynamic and flexible energy ecosystem, potentially leading to more efficient resource allocation and pricing mechanisms [31-32]. The integration of solar energy into smart grids is not without challenges. Issues such as cybersecurity, data privacy, and the need for significant infrastructure investments must be addressed. The complexity of managing a highly distributed and variable energy source like solar power requires sophisticated control algorithms and decision-making systems, which is where AI comes into play as a crucial enabling technology. AI-driven predictive analytics has emerged as a powerful tool in addressing the challenges of solar energy variability and improving overall system efficiency. By leveraging machine learning algorithms and big data analytics, AI can provide highly accurate forecasts of solar irradiance and energy output, enabling more effective planning and management of solar energy systems [22,24,33-34].

One of the primary applications of AI-driven predictive analytics in solar energy management is short-term forecasting. These forecasts, which typically cover periods from a few minutes to several hours ahead, are crucial for real-time grid management and energy trading. Machine learning models, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) and support vector machines (SVMs), have shown remarkable accuracy in predicting solar irradiance and power output based on historical data and current weather conditions [35]. For instance, Najeeb, Aboshosha, and; Poudyal demonstrated the effectiveness of a hybrid CNN-LSTM (Convolutional Neural Network - Long Short-Term Memory) model in forecasting solar irradiance with high accuracy up to 6 hours ahead [36-37]. Their model outperformed traditional statistical methods, showcasing the potential of DL models in capturing complex patterns in solar data. AI-driven predictive analytics also plays a crucial role in longer-term forecasting, which is essential for capacity planning and investment decisions in solar energy projects. By analyzing long-term weather patterns, seasonal variations, and other relevant factors, AI models can provide insights into expected energy production over months or even years. This information is invaluable for project developers, investors, and policymakers in assessing the viability and potential returns of solar energy investments [7,38] . Moreover, AI-driven analytics can enhance the accuracy of solar resource assessment, a critical factor in site selection and system design for solar installations. By integrating multiple data sources, including satellite imagery, ground measurements, and topographic data, machine learning algorithms can create high-resolution maps of solar potential across large geographic areas. This enables more informed decision-making in the planning and development of solar energy projects [39,26]. Another important application of AI-driven predictive analytics is in the optimization of energy storage systems. By accurately forecasting solar power generation and energy demand, AI algorithms can determine optimal charging and discharging strategies for battery systems, maximizing the utilization of solar energy and reducing reliance on grid power [40].

System Optimization

System optimization in the context of solar energy management refers to the process of maximizing the efficiency, output, and overall performance of solar energy systems through the application of advanced analytical techniques, including AI. This concept encompasses a wide range of optimization strategies that target various aspects of solar energy systems, from panel layout and orientation to inverter efficiency and energy storage management [36]. One of the primary areas of system optimization in solar energy is the design and layout of solar panel arrays. AI algorithms can analyze factors such as local topography, shading patterns, and expected weather conditions to determine the optimal arrangement and tilt angle of solar panels. This optimization can significantly increase energy yield, particularly in complex installations such as those on uneven terrain or in urban environments with partial shading [27,41-42]. Te, Mengze, and Yan demonstrated the use of a genetic algorithm combined with a 3D shading model to optimize the layout of a large-scale photovoltaic plant [2]. Their approach resulted in a 5.28% increase in annual energy output compared to traditional design methods, highlighting the potential of AI-driven optimization in improving system performance.

Another critical aspect of system optimization is the management of inverters, which convert the DC power generated by solar panels into AC power for grid use. AI algorithms can optimize inverter operations in real-time, adjusting parameters such as maximum power point tracking to maximize energy conversion efficiency under varying environmental conditions [1]. Energy storage optimization is also a key component of overall system optimization. AI can play a crucial role in determining optimal charging and discharging strategies for battery systems, considering factors such as expected solar generation, energy demand patterns, and electricity pricing. This can help maximize the use of solar energy, reduce reliance on grid power during peak demand periods, and potentially generate additional revenue through energy arbitrage [43]. Moreover, AI-driven system optimization extends to the integration of solar energy with other renewable sources and smart grid technologies. By analyzing data from multiple sources, AI algorithms can optimize the coordination between solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources, as well as demand response programs, to create a more stable and efficient overall energy system [44]. Predictive maintenance is another area where system optimization through AI can yield significant benefits. By analyzing performance data from various components of a solar energy system, machine learning algorithms can predict potential failures or performance degradation. This allows for proactive maintenance, reducing downtime and extending the lifespan of system components [45-46].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Energy Systems

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in energy systems represents a transformative approach to managing and optimizing energy production, distribution, and consumption. In the context of solar energy, AI technologies are being leveraged to address the unique challenges posed by the variability and intermittency of solar power, as well as to enhance overall system efficiency and reliability [3,40,47]. AI in energy systems encompasses a wide range of technologies and approaches, including ML, DL, natural language processing, and computer vision. These technologies are being applied across various aspects of energy management, from generation forecasting and grid optimization to demand response and energy trading [45,48]. One of the primary applications of AI in solar energy systems is in forecasting and prediction. Machine learning algorithms, particularly DL models, have shown remarkable accuracy in predicting solar irradiance and power output. These predictions are crucial for grid operators in managing the integration of solar power into the broader energy mix. Barua et al demonstrated the use of a hybrid CNN-LSTM model for ultra-short-term photovoltaic power forecasting, achieving higher accuracy than traditional statistical methods [4].

AI is also playing a significant role in optimizing the design and operation of solar energy systems. Through techniques such as reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms, AI can determine optimal configurations for solar panel arrays, maximizing energy yield based on local conditions. Similarly, AI algorithms can optimize the operation of inverters and energy storage systems, enhancing overall system efficiency [49-50]. In the context of grid management, AI is enabling more sophisticated control strategies for integrating variable renewable energy sources like solar. Machine learning algorithms can analyze vast amounts of data from diverse sources – including weather forecasts, energy consumption patterns, and market prices – to optimize grid operations in real-time. This can help balance supply and demand, reduce the need for backup power sources, and ultimately increase the share of renewable energy in the overall energy mix [6-7]. AI is also transforming energy trading and market operations. Through the analysis of historical data and real-time market conditions, AI algorithms can develop optimal bidding strategies for solar energy producers participating in electricity markets. Moreover, AI is enabling the development of peer-to-peer energy trading platforms, allowing prosumers to directly trade excess solar energy with other consumers [9-10]. In the realm of energy efficiency and demand management, AI is facilitating more sophisticated demand response programs. By analyzing consumption patterns and predicting future demand, AI systems can automatically adjust energy usage in smart buildings or industrial processes to align with periods of high solar energy production [11].

Weather Conditions and Solar Power Generation

The relationship between weather conditions and solar power generation is a critical aspect of solar energy management, significantly influencing the reliability and efficiency of solar power systems. Understanding and accurately predicting this relationship is essential for effective integration of solar energy into the broader energy mix and for optimizing system performance [12,47,51]. Solar irradiance, which is directly affected by weather conditions, is the primary factor determining solar power output. Cloud cover, in particular, has a substantial impact on solar energy generation. Even partial cloud cover can lead to rapid fluctuations in power output, creating challenges for grid stability and energy management. These fluctuations can occur on timescales ranging from seconds to hours, necessitating sophisticated forecasting and control systems [14-15]. Temperature is another crucial weather parameter affecting solar panel efficiency. While higher temperatures increase solar irradiance, they also reduce the efficiency of photovoltaic cells. This inverse relationship between temperature and panel efficiency means that extremely hot days may not necessarily result in peak solar energy production. Understanding and modeling this temperature dependence is crucial for accurate power output predictions and system design optimization [16].

Seasonal variations in weather patterns have long-term implications for solar energy production. In many regions, winter months see significantly reduced solar energy output due to shorter days and less direct sunlight. This seasonal variability must be accounted for in long-term energy planning and in the design of energy storage and backup systems [18]. Other weather conditions, such as humidity, wind speed, and atmospheric particulate matter, also influence solar power generation. High humidity can reduce solar irradiance through increased scattering of sunlight, while wind speed affects panel temperature and can impact energy yield. Atmospheric pollution and dust accumulation on panels can significantly reduce their efficiency over time [19]. The complex and dynamic nature of weather's impact on solar power generation underscores the importance of advanced forecasting techniques. AI and machine learning algorithms have shown great promise in improving the accuracy of weather-based solar power predictions. These models can integrate data from multiple sources, including satellite imagery, ground-based sensors, and numerical weather prediction models, to provide more accurate and timely forecasts of solar energy production [20].

System Design Parameters in Solar Energy

System design parameters play a crucial role in determining the efficiency, reliability, and overall performance of solar energy systems. These parameters encompass a wide range of factors, from the physical layout and orientation of solar panels to the selection of inverters, energy storage systems, and grid integration technologies. Optimizing these parameters is essential for maximizing energy yield and ensuring the economic viability of solar installations [22]. One of the primary system design parameters is the tilt angle and orientation of solar panels. These factors significantly influence the amount of solar radiation captured by the panels throughout the day and across seasons. While the optimal tilt angle generally corresponds to the latitude of the installation site, local factors such as shading, weather patterns, and land constraints may necessitate adjustments. AI-driven optimization algorithms can analyze these factors to determine the ideal panel configuration for a given location [23]. Panel type and technology selection is another critical design parameter. The choice between monocrystalline, polycrystalline, or thin-film solar cells, as well as considerations of bifacial panels or concentrated photovoltaic systems, can significantly impact system performance and cost-effectiveness. AI can aid in this selection process by analyzing performance data across various environmental conditions and projecting long-term energy yields and financial returns [23].

Inverter selection and configuration also play a vital role in system design. The choice between string inverters, microinverters, or power optimizers can affect system efficiency, particularly in scenarios with partial shading or complex roof geometries. AI algorithms can optimize inverter selection and configuration based on specific installation characteristics and expected operating conditions [36]. Energy storage system design is becoming increasingly important as solar penetration grows. The capacity, type, and control strategy of battery systems must be carefully optimized to balance factors such as self-consumption maximization, peak shaving, and grid support services. AI can assist in sizing storage systems and developing intelligent control strategies that adapt to changing energy production and consumption patterns [44]. Grid integration parameters, including power quality control systems and grid-tie technologies, are crucial for ensuring the stable and efficient connection of solar systems to the broader power grid. These parameters must be designed to meet local grid codes and regulations while maximizing the value of solar energy production [10,51]. The optimization of these system design parameters is a complex task that must consider multiple, often conflicting objectives. AI and machine learning techniques offer powerful tools for navigating this complexity, enabling more holistic and adaptive approaches to solar system design that can significantly enhance performance and cost-effectiveness.

Theoretical Framework

Systems Framework

Systems Framework provides a valuable framework for understanding and analyzing the complex interactions within solar energy management systems, particularly in the context of AI applications. This framework, which emphasizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of various components within a system, offers insights into how solar energy systems can be optimized and integrated into broader energy networks [4,52]. In the context of solar energy management, Systems framework helps to conceptualize the solar energy infrastructure as a complex adaptive system composed of multiple interconnected subsystems. These subsystems include solar panels, inverters, energy storage devices, smart grid components, weather systems, and energy markets, among others. The behavior of the overall system emerges from the interactions between these components, often in non-linear and sometimes unpredictable ways [32]. One key principle of Systems framework particularly relevant to solar energy management is the concept of feedback loops. In solar energy systems, various feedback mechanisms operate at different scales. For instance, the output of solar panels influences grid stability, which in turn affects energy pricing and consumption patterns, ultimately feeding back to impact solar energy production and storage strategies. AI algorithms can be designed to recognize and optimize these feedback loops, enhancing overall system performance [24].

Another important aspect of Systems framework in this context is the idea of system boundaries and interactions with the environment. Solar energy systems are not closed systems; they are heavily influenced by external factors such as weather conditions, energy policies, and technological advancements. AI applications in solar energy management must therefore be designed with an understanding of these system boundaries and the ability to adapt to changing external conditions [25]. The concept of emergence in Systems framework is also relevant to AI applications in solar energy management. The collective behavior of numerous distributed solar installations, when integrated through smart grid technologies and managed by AI algorithms, can give rise to emergent properties at the grid level. These emergent behaviors, such as increased grid resilience or more efficient energy distribution, are not predictable from the properties of individual components alone [19,53]. Systems framework also emphasizes the importance of considering multiple perspectives and stakeholders in system analysis and design. In the context of solar energy management, this translates to the need for AI systems that can balance the diverse and sometimes conflicting objectives of different stakeholders, including energy producers, consumers, grid operators, and policymakers [19]. Furthermore, the systems thinking approach encourages a holistic view of problem-solving, which aligns well with the capabilities of AI in handling complex, multi-variable optimization problems. AI algorithms can be designed to consider the entire system's performance rather than optimizing individual components in isolation, leading to more effective and sustainable solutions [26].

Machine Learning Model

Machine Learning models forms a cornerstone of AI applications in solar energy management, providing the theoretical basis for developing algorithms that can learn from data, identify patterns, and make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed for these tasks. This theoretical framework encompasses various approaches to machine learning, including supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning, each with its own set of principles and applications in the context of solar energy management [16,27]. Supervised learning, a key component of ML models, is particularly relevant in solar energy forecasting and system performance prediction. In this approach, algorithms are trained on labeled datasets, learning to map input features (such as weather data or historical energy production) to output variables (such as future energy production). The theoretical foundations of supervised learning, including concepts like empirical risk minimization and regularization, guide the development of models that can generalize well to new, unseen data [28,32]. Support vector machines (SVMs) and ANNs, both grounded in supervised learning models, have been widely applied in solar irradiance and power output forecasting. The models behind these models provides insights into their capacity to capture complex, non-linear relationships in solar energy data, as well as strategies for avoiding overfitting and improving generalization [29].

Unsupervised learning models, which deals with finding patterns or structures in unlabeled data, is valuable in applications such as anomaly detection in solar panel performance or clustering of energy consumption patterns. Techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) and k-means clustering, underpinned by unsupervised learning models, can reveal hidden patterns in solar energy data that may not be apparent through traditional analysis methods [29,31,33]. Reinforcement learning models, which focuses on how agents can learn to make decisions by interacting with an environment, has significant potential in optimizing solar energy system operations. This theoretical framework provides the basis for developing algorithms that can learn optimal control strategies for energy storage systems or smart inverters, adapting to changing environmental conditions and energy market dynamics over time [32]. The concept of feature learning, a fundamental aspect of ML models, is particularly relevant in solar energy applications. The DL models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, can automatically learn relevant features from raw data, potentially uncovering subtle patterns in solar irradiance or system performance that might be missed by traditional feature engineering approaches [26].

Statistical learning models which provided a mathematical framework for understanding the learning process and the generalization capabilities of machine learning models, is crucial in developing robust and reliable AI systems for solar energy management. Concepts such as the bias-variance tradeoff and the VC dimension help in understanding the limitations and capabilities of different machine learning models in the context of solar energy applications [27]. Ensemble learning models, which deals with combining multiple models to improve prediction accuracy and robustness, is particularly valuable in solar energy forecasting. Techniques like random forests and gradient boosting, grounded in ensemble learning models, can often outperform single models in predicting solar irradiance and power output, especially in complex and variable environments [28]. Transfer learning models, which explores how knowledge gained from one task can be applied to a different but related task, has significant potential in solar energy applications. This theoretical framework can guide the development of models that can adapt to new locations or system configurations with minimal additional training, potentially reducing the data requirements and improving the generalization of AI models in solar energy management [30]. To this end, ML models provides a rich and diverse theoretical foundation for developing AI applications in solar energy management. It offers insights into how to design, train, and evaluate models that can effectively learn from solar energy data, make accurate predictions, and optimize system performance. As the field continues to evolve, new theoretical developments in machine learning are likely to open up further possibilities for enhancing the efficiency and reliability of solar energy systems through AI.

Optimization Algorithms

Optimization algorithms provides a crucial theoretical foundation for many AI applications in solar energy management, offering a framework for developing algorithms that can find the best solutions to complex problems involving multiple variables and constraints. In the context of solar energy systems, optimization algorithms guides the development of AI algorithms that can maximize energy output, minimize costs, and improve overall system efficiency [22,27,54]. One of the key concepts in optimization algorithms relevant to solar energy management is multi-objective optimization. Solar energy systems often involve multiple, sometimes conflicting objectives, such as maximizing energy production while minimizing costs and environmental impact. Multi-objective optimization algorithms provides the basis for developing algorithms that can find Pareto-optimal solutions, balancing these different objectives in an optimal way [35]. For instance, in the design of large-scale solar farms, multi-objective optimization can be used to simultaneously consider factors such as land use, shading effects, cable routing, and maintenance accessibility. AI algorithms based on multi-objective optimization algorithms can navigate this complex decision space to find optimal system configurations [38-39]. Convex optimization algorithms, which deals with problems where the objective function and constraints are convex, is particularly useful in certain aspects of solar energy management. For example, in energy storage optimization, the problem of determining optimal charging and discharging strategies can often be formulated as a convex optimization problem, allowing for efficient solution methods [55].

Nonlinear programming algorithms is crucial in many solar energy optimization problems where the relationships between variables are not linear. This is often the case in solar panel orientation optimization or in modeling the complex relationships between weather variables and solar power output. AI algorithms based on nonlinear programming algorithms can handle these complex, nonlinear relationships to find optimal solutions [56]. Stochastic optimization algorithms is particularly relevant in solar energy management due to the inherent uncertainties in weather conditions and energy demand. This theoretical framework provides the basis for developing algorithms that can make optimal decisions in the face of uncertainty, such as in day-ahead scheduling of solar power generation or in managing energy storage systems [3,57-58]. Dynamic programming, a method for solving complex problems by breaking them down into simpler subproblems, has numerous applications in solar energy optimization. For instance, in optimizing the operation of a solar-plus-storage system over time, dynamic programming can be used to develop strategies that consider both current conditions and future expectations [5,59]. Integer programming algorithms is valuable in problems involving discrete decisions, such as the selection and placement of solar panels or inverters in a large-scale installation. AI algorithms based on integer programming can handle these combinatorial optimization problems, finding optimal configurations from a vast number of possible combinations [8].

Global optimization algorithms, which deals with finding the absolute best solution in problems that may have multiple local optima, is crucial in many solar energy applications. For example, in optimizing the layout of a solar farm on complex terrain, global optimization techniques can help avoid getting stuck in suboptimal local solutions [54]. Metaheuristic optimization techniques, such as genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization, and simulated annealing, provide powerful tools for solving complex optimization problems in solar energy management. These techniques, inspired by natural processes, can effectively explore large solution spaces and find near-optimal solutions to problems that may be intractable for traditional optimization methods [38]. Robust optimization algorithms is particularly relevant in solar energy applications due to the variability and uncertainty inherent in renewable energy systems. This theoretical framework provides the basis for developing optimization algorithms that can find solutions that perform well across a range of possible scenarios, enhancing the resilience and reliability of solar energy systems [25]. Thus, Optimization algorithms provides a rich theoretical foundation for developing AI applications in solar energy management. It offers a diverse set of tools and approaches for solving the complex optimization problems that arise in designing, operating, and managing solar energy systems. As the field continues to evolve, advances in optimization algorithms are likely to enable even more sophisticated and effective AI applications in solar energy management.

Empirical Review

The application of AI in solar energy management has been the subject of numerous empirical studies in recent years, demonstrating the practical benefits and challenges of implementing these technologies. This empirical review synthesizes findings from various studies, highlighting key areas where AI has shown promise in enhancing solar energy management. One of the most extensively studied applications of AI in solar energy management is in forecasting and prediction. Khosrojerdi et al. conducted a comprehensive study comparing various machine learning models for ultra-short-term photovoltaic power forecasting. Their results showed that a hybrid CNN-LSTM model outperformed traditional statistical methods, achieving a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of less than 2% for 15-minute ahead forecasts [6]. This level of accuracy represents a significant improvement over conventional forecasting techniques, potentially enabling more efficient grid integration of solar power. Similarly, Tandon et al demonstrated the effectiveness of a DL approach for solar irradiance forecasting [51]. Their model, which combined CNNs with LSTM networks, achieved high accuracy in predicting solar irradiance up to 6 hours ahead. The study highlighted the ability of DL models to capture complex temporal and spatial patterns in solar data, leading to more reliable forecasts. AI has also shown significant potential in optimizing various aspects of solar energy systems. Khosrojerdi et al. applied a genetic algorithm combined with a 3D shading model to optimize the layout of a large-scale photovoltaic plant [6]. Their approach resulted in a 5.28% increase in annual energy output compared to traditional design methods, demonstrating the potential of AI in enhancing system performance through improved design. Energy storage optimization, [60-61] developed a reinforcement learning algorithm for managing battery systems in solar-plus-storage installations. Their model learned to optimize charging and discharging strategies based on solar generation forecasts, electricity prices, and load demands. The study reported a 15% reduction in electricity costs compared to rule-based control strategies, showcasing the economic benefits of AI-driven optimization [36].

Despite the promising advancements in AI applications for solar energy management highlighted in the reviewed literature, several existing limitations persist. Data quality and availability remain a significant challenge, as many studies rely on fragmented, inconsistent, or incomplete datasets from solar systems, which hinder the effective training and generalization of AI models [6,12]. The lack of interpretability in advanced techniques, such as DL and hybrid CNN-LSTM models, often renders them as "black boxes," leading to skepticism among stakeholders regarding critical decision-making for grid stability and system performance [4,13]. High computational demands and the need for significant upfront investments in infrastructure and expertise limit widespread adoption, particularly for smaller-scale installations or in developing regions [14,33]. Additionally, many empirical studies are based on synthetic or location-specific datasets with simplified assumptions, reducing their real-world applicability under highly variable weather conditions or complex grid integrations [15,36]. Finally, overfitting risks and discrepancies between cross-validation and test performance indicate challenges in model robustness across diverse environmental scenarios [51].

METHODOLOGY

Research Approach

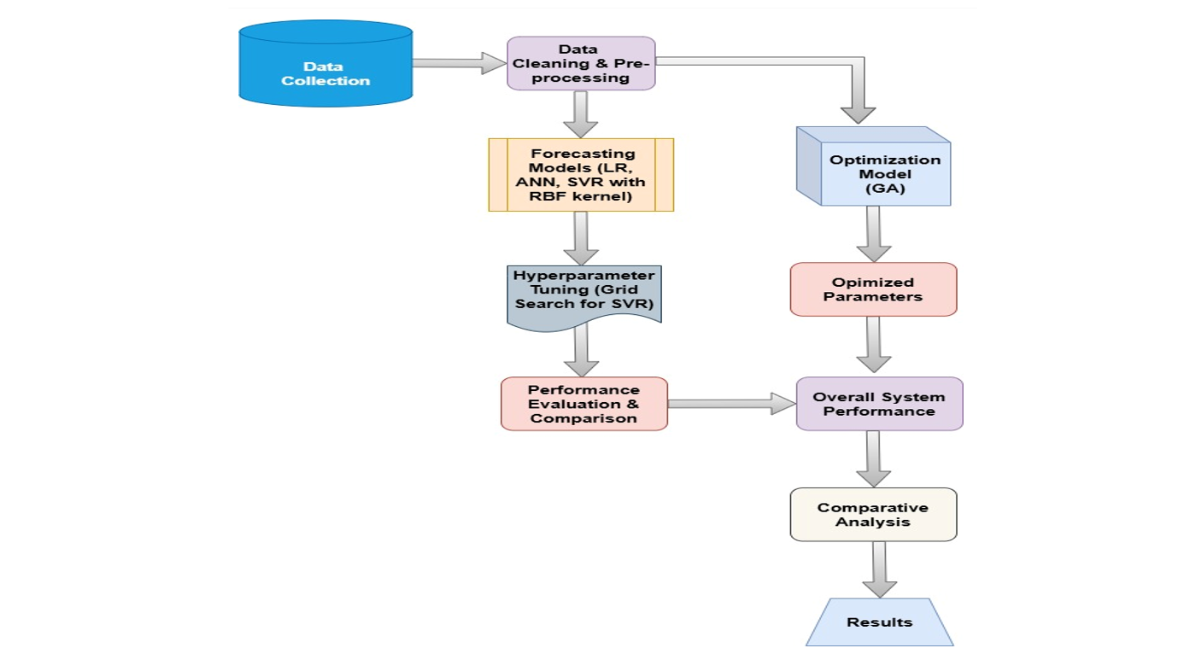

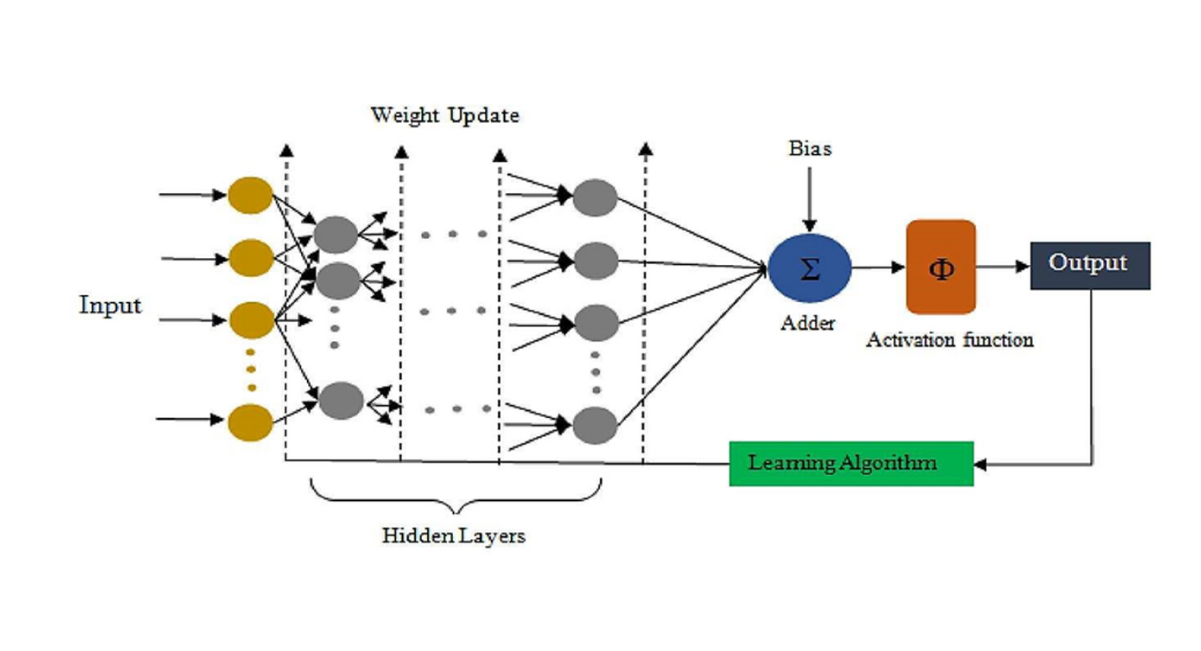

This study investigates the application of AI in solar energy management, focusing on evaluating advanced algorithms for predicting solar energy output and optimizing system efficiency under varying weather conditions and complex designs. Accurate solar irradiance forecasting is critical for enhancing energy generation and grid integration. Machine learning techniques, particularly Support Vector Regression (SVR), excel in capturing non-linear relationships in meteorological data, outperforming traditional statistical methods, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and persistence models across diverse conditions in Fig. 1. Ensemble methods like Random Forests and Gradient Boosting further improve forecast accuracy by combining multiple models to adapt to changing atmospheric patterns, leveraging historical data and satellite imagery for robust short- and long-term predictions [54].

The methodology combines prediction, forecasting, and optimization techniques, utilizing a unified dataset and MATLAB algorithm to tackle three objectives. It first assesses how advanced AI algorithms (e.g. DL and NN) enhance solar energy output and efficiency compared to simpler ones, accounting for weather and system design. Next, it explores how varying weather conditions affect AI algorithm performance in boosting solar output and efficiency, regardless of algorithm complexity. Finally, it examines AI optimization of solar energy in complex designs (e.g., multi-orientation arrays) versus simpler setups, controlling for weather. Cohesiveness is maintained through a consistent dataset and metrics, covering data collection, preprocessing, algorithm selection, model development, experiments, and evaluation [54].

Figure 1: Research methodology

Data Collection

A unified dataset supports prediction, forecasting, and optimization tasks for solar energy management, ensuring consistent evaluation across objectives. It includes weather data (solar irradiance, temperature, time) from a reliable meteorological database, covering hourly records over 2022–2025 across diverse climates (arid, temperate, tropical) to capture variability. Solar system data encompasses simple fixed-tilt PV arrays and complex multi-orientation arrays with monocrystalline panels and energy storage, including parameters like tilt angle (0°–90°), azimuth (0°–360°), panel efficiency (30%), inverter efficiency (70%), storage capacity, and historical energy output. Sourced from PVWatts simulations and real-world installations, the dataset comprises ~26,280 hourly records per location (minimum three locations) and is stored in CSV format for MATLAB compatibility.

Data Preprocessing

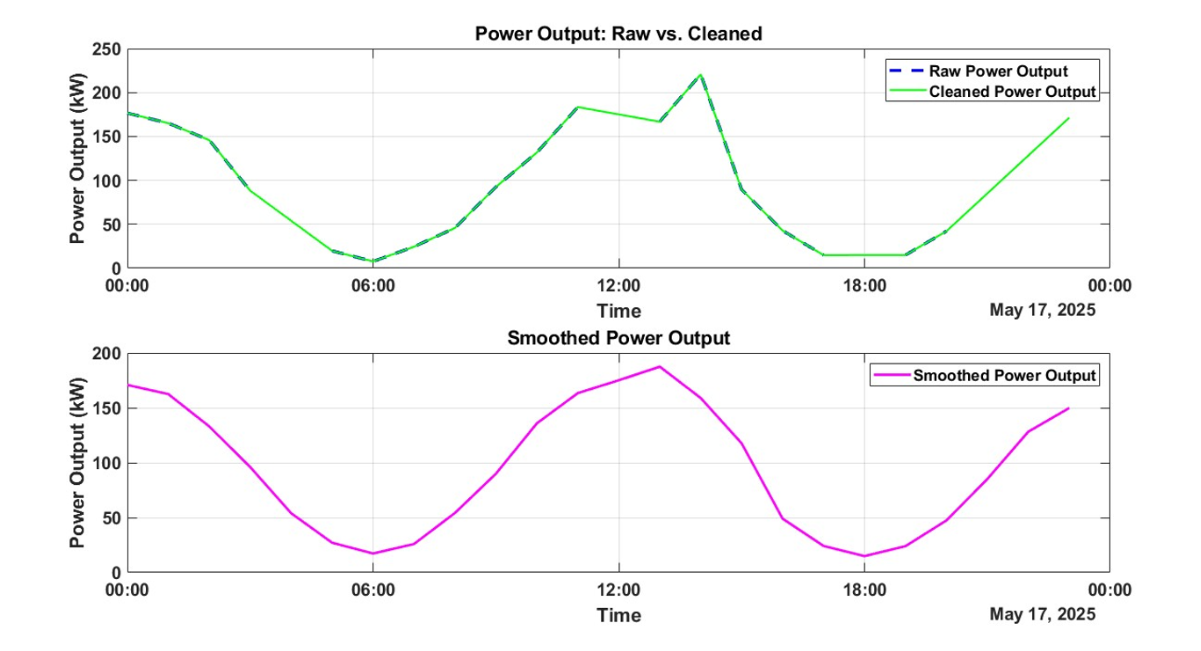

The data cleaning and preprocessing pipeline involves three key steps: handling missing values, removing outliers, and smoothing noisy data. Missing values in solar irradiance, power output, and temperature are filled using linear interpolation via MATLAB’s fillmissing function, preserving temporal trends. Outliers in power output, detected using the IQR method (isoutlier), are replaced with NaN and interpolated to ensure continuity. A moving average filter (movmean) smooths noise in the power output, enhancing data quality for ANN training [62]. To enhance data quality for AI modeling, a moving average filter (window size of three) was applied to the power output using the movmean function, reducing noise while preserving trends. Fig. 2 shows two subplots: one comparing raw and cleaned power output with outliers marked as red circles, and another displaying the smoothed power output, illustrating noise reduction.

Figure 2: The raw and cleaned Power Output

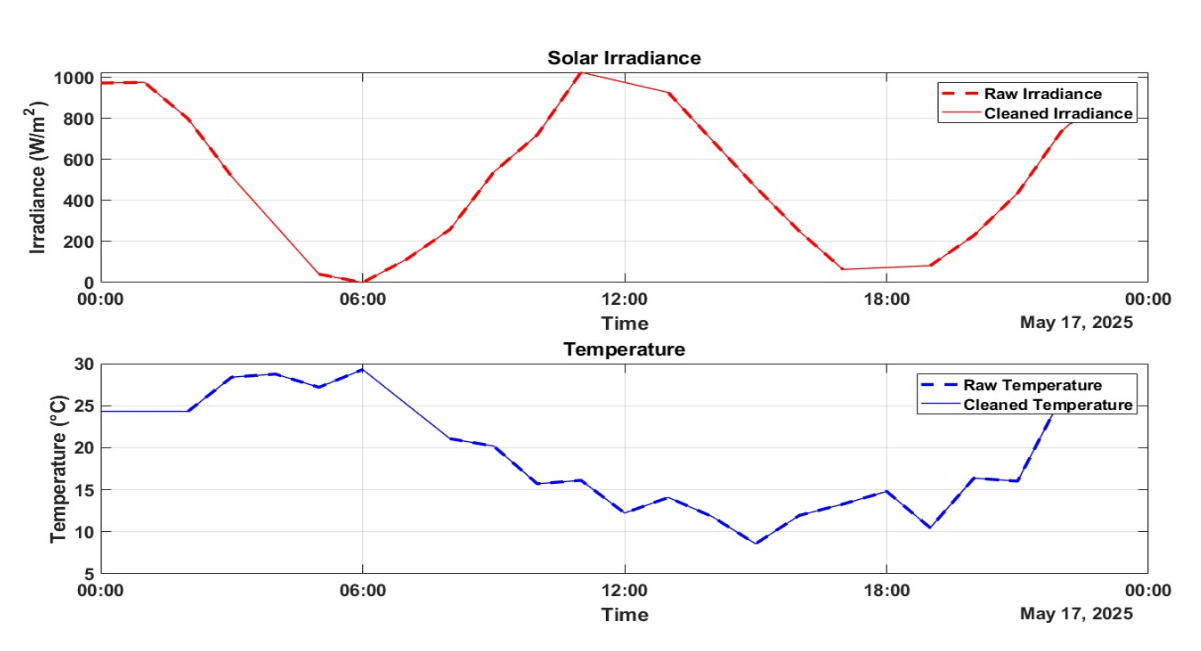

Figure 3 displays raw and cleaned solar irradiance and temperature data in separate subplots, with raw data as dotted lines and cleaned data as solid lines. By addressing missing values, outliers, and noise, the pipeline ensures a robust dataset for training machine learning models, like neural networks or regression models, to predict power output or optimize energy storage [56]. The synthetic dataset enables controlled testing of the data cleaning process, with methods directly applicable to real-world solar energy datasets that often have similar issues like missing values and outliers. The modular, customizable algorithm allows researchers to adjust parameters such as smoothing window size or outlier thresholds to suit specific datasets. The cleaned dataset is saved in a format ready for AI workflows, supporting applications like solar power forecasting and grid optimization.

Figure 3: The raw and cleaned solar irradiance and temperature

AI Algorithms Selection

This research leverages AI to enhance solar energy management by addressing three objectives using DL and Global Optimization Toolboxes. It compares advanced AI, like deep neural networks, with simpler models, such as linear regression, to evaluate energy output and efficiency under varying weather conditions. It also assesses AI algorithm robustness across diverse weather scenarios and optimizes complex system designs, like multi-orientation arrays, for scalability and adaptability. Through prediction, forecasting, and optimization, the study delivers insights for sustainable solar energy solutions.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

ANNs are feedforward neural networks with multiple hidden layers, designed to model complex, non-linear relationships between inputs (e.g., weather data, system parameters) and outputs (e.g., energy production). Their ability to capture intricate patterns makes them ideal for evaluating performance under controlled conditions and adapting to variable weather scenarios [62].

Support Vector Regression (SVR)

SVR is a robust non-linear regression model that serves as a benchmark for comparing advanced DL methods like ANNs. Its inclusion ensures a balanced assessment of algorithm performance, particularly in where it provides a middle ground between simplicity and complexity [32].

Genetic Algorithms (GA)

GAs is employed to optimize system parameters such as panel tilt, azimuth, and storage scheduling in complex solar energy designs. Their evolutionary approach excels in navigating large, intricate search spaces, making them well-suited for. By exploring multiple solution candidates simultaneously, GAs can identify near-optimal configurations that enhance energy output and efficiency in multi-orientation arrays and diverse panel setups [56]. ANNs, SVR, and LR are evaluated under controlled conditions to assess their impact on solar energy output and efficiency, with ANNs and SVR expected to outperform LR due to their ability to model non-linear relationships in fluctuating weather and varied system designs [56]. LR serves as a baseline to quantify the benefits of advanced algorithms, weighing their computational costs against performance gains. ANNs and SVR’s capacity to adapt to complex patterns is anticipated to show greater resilience than LR, critical for maintaining high performance in unpredictable real-world weather conditions [55]. Genetic Algorithms (GAs) optimize parameters in complex solar energy systems, accounting for weather conditions to maximize efficiency in multi-orientation arrays and diverse panel types. This highlights AI’s transformative potential in designing and operating advanced solar installations.

Model Development

All models are developed in MATLAB, leveraging its specialized toolboxes ML and optimization.

Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Predicting

The ANNs is inspired by biological neurons, map uncertain inputs to outputs without complex equations. Learning from data, ANNs efficiently handle control factors, ideal for solar energy prediction. For regression tasks, multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) or feedforward networks process data with minimal computational effort, ensuring accurate predictions.

The network consists of:

- Input Layer: Features like solar irradiance, temperature, and time of day.

input vector [ x = x 1 , x 2 , … , x n ] T where are the features of the irradiance, temperature and time taken

- Hidden Layers: Nodes that transform inputs using weights, biases, and activation functions to capture non-linear patterns.

◦ Number of nodes: ( m ) ,

◦ Weights: W (1) ∈ ℝ m × n , biases: b (1) ∈ ℝ m

Activation function: ReLU , σ ( z ) = max ( 0 , z ) , or sigmoid σ ( z ) = 1 1 + e − s

◦ Hidden layer output: h = σ ( W ( 1 ) x + b ( 1 ) )

- Output Layer: Predicted value, e.g., PV power output (in kW).

◦ Weights: W (2) ∈ ℝ 1 × m , biases: b (2) ∈ ℝ ,

◦ Predicted output (for regression, typically linear activation): y ^ = W (2) h + b (2) .

- Loss function: mean square error (MSE) as shown in Equation 1.

Loss = 1 N ∑ i 1 N ( y i − y ^ i ) 2 (1)

where y i is the actual output, y ^ i is the predicted output, and N is the number of samples [11] .

Supervised training involves using imported data to train an ANN, which consists of interconnected neurons, akin to those in the human brain. Each neuron's weight, a fractional value, defines the strength of connections between them, enabling the ANN to learn patterns for solar energy output prediction [32,63]. In an ANN, neurons across the input, hidden, and output layers are interconnected by adjustable weights, which are refined during training to minimize prediction errors until an acceptable error level is achieved, stabilizing the weights. As depicted in Fig. 4, the ANN structure comprises three layers: the input layer, with neurons determined by input parameters (e.g., solar irradiance, temperature); hidden layers, with neuron counts set via trial-and-error; and the output layer, with neurons based on output parameters (e.g., power output). A bias parameter adjusts the network’s output, and ‘t’ denotes time in dynamic models.

Figure 4: ANN architecture [26]

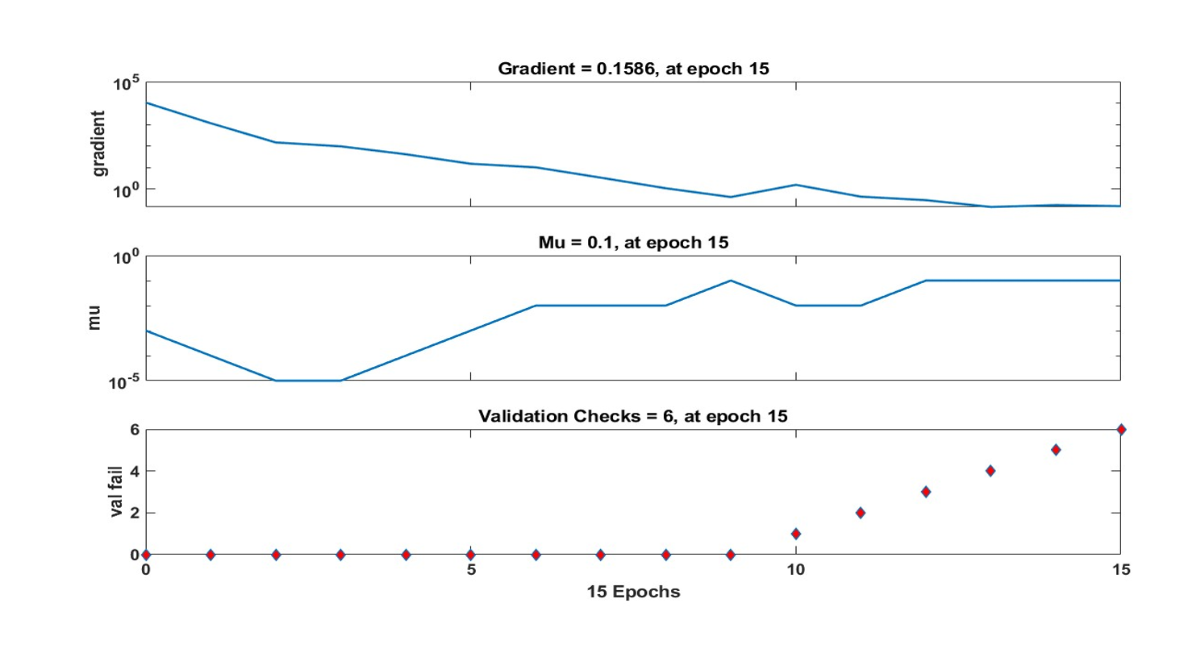

The ANN for predicting solar energy output, central to the study using the DL Toolbox (Fig. 5). The ANN, with two input neurons (solar irradiance, temperature), three hidden layers (100, 50, 25 neurons, ReLU activation), and one output neuron (linear activation), predicts power output. Trained with backpropagation using the Adam optimizer (or Levenberg-Marquardt fallback) for 100 epochs and an approximated batch size of 32, it addresses energy forecasting challenges. The ANN training state of 15 Epoch is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: ANN Training State, Epoch 15

A synthetic dataset simulating solar energy parameters over 10 days (May 17–26, 2025) with hourly measurements (240 samples) includes solar irradiance (W/m²), power output (kW), and temperature (°C). Solar irradiance follows a squared sine function to mimic daily cycles, with Gaussian noise and 5% missing values. Power output, derived at 18% of irradiance, includes noise, 3% missing values, and 2% outliers. Temperature uses a sine function peaking in the afternoon, with noise and 3% missing values. The dataset enables ANN testing while mirroring real-world data imperfections.

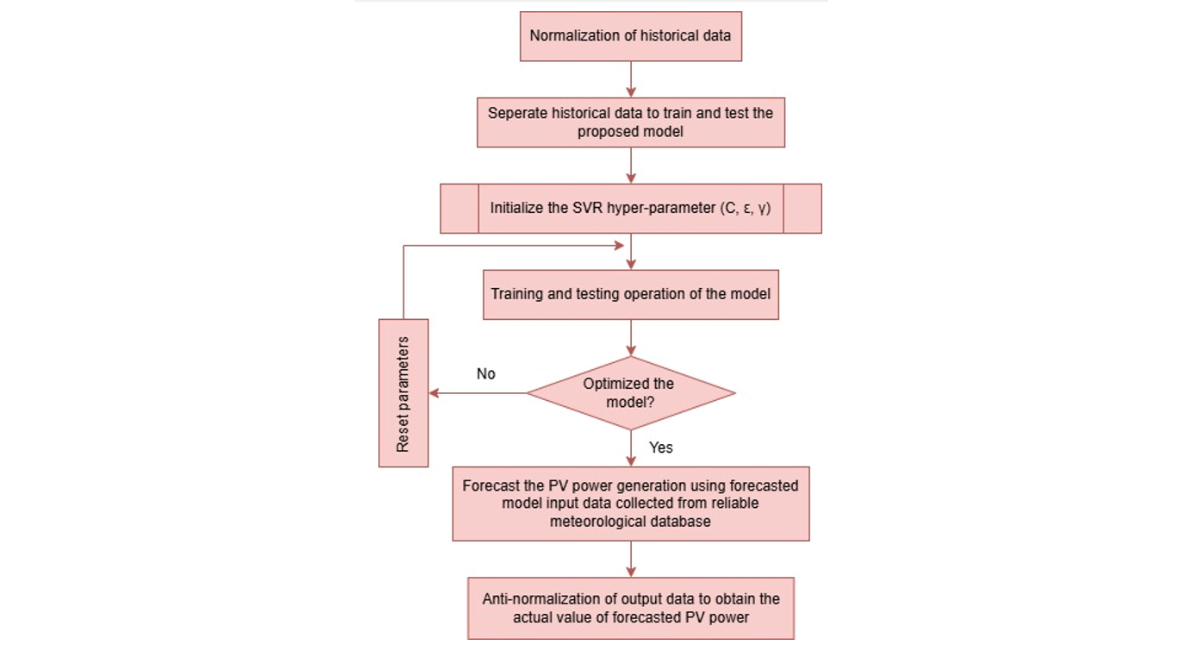

Support Vector Machine (SVM) Forecasting

Support Vector Regression (SVR), an AI technique, boosts solar energy efficiency by forecasting power output using meteorological data and detecting anomalies in PV systems. SVR predicts outputs within a tolerance margin, minimizing complexity, and uses a kernel trick to handle non-linear relationships in higher-dimensional spaces.

Mathematical Formulation:

For the dataset { ( x i , y i ) } i = 1 N , where x i are input features and y i are the target values .

Using, a kernel function K ( x i , x j ) which is radial basis function (RBF) kernel: K ( x i , x j ) = exp ( − γ ∥ x i − x j ∥ 2 ) and the Model shown in Equation 2 f ( x ) = ∑ i 1 N ( α i − α * i ) K ( x i , x ) + b , where α i , α * i (2)

are Lagrange multipliers. The dual optimization is solved to find α , α * i , and only support vectors (points where α i ≠ 0 ) contribute to the model [29,31,33] .

The SVR model uses a time-series dataset with Solar Irradiance (W/m²), Temperature (°C), and Power Output (kW) to predict solar power generation for grid stability and energy management. Support Vector Regression (SVR) fits a hyperplane to non-linear data, minimizing errors within an ε-tube. Hyperparameters (C, ε, γ) are tuned via grid search with 5-fold cross-validation shows in Fig. 6. This approach enhances solar energy forecasting reliability.

Figure 6: SVM framework for solar energy prediction [55]

SVM regression starts with selecting a kernel (linear, polynomial, RBF) to transform data into a higher-dimensional space. The model is trained to find the optimal hyperplane, minimizing error via SVR optimization. Performance is evaluated using validation techniques and metrics like MSE, MAE, or R². The trained model predicts continuous outputs for new data, resisting overfitting through its margin parameter. Data preprocessing involves loading data, verifying columns (Time, Solar Irradiance, Temperature, Power Output), converting Time to date-time, normalizing features with z-score, and splitting data (80% training, 20% testing) with a fixed seed for reproducibility.

Genetic Algorithm Optimization for Solar Energy Management

Genetic algorithm (GA)-based regression excels in optimizing complex, non-linear, or discontinuous search spaces where traditional methods struggle to find global optima. Ideal for poorly understood input-output relationships and multi-modal fitness landscapes, GAs optimize photovoltaic (PV) system design, panel placement, and energy storage scheduling. They efficiently determine optimal configurations, like solar panel tilt and orientation, to maximize energy capture under diverse conditions. As evolutionary algorithms, GAs evolve a population of candidate solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation to optimize objective functions, making them well-suited for non-linear, multi-objective optimization problems with intricate constraints in solar energy management.

Mathematical Functions:

Chromosome: A solution vector x = [ θ , Ø ] , where θ is the panel tilt angle (0 ° to 90 ° ) and Ø is the orientation (azimuth, -180 ° to 180 ° ).

Objective Function: Maximize energy output, computed as Equation 3.

E = ∑ t = 1 T P t , P t = G t ⋅ η ⋅ A ⋅ max ( cos ( φ t ) , 0 ) (3)

Where: (E): Total energy output (kWh) over time period (T).

Pt: Power output at time (t)

Gt: Global horizontal irradiance (W/m²) at time (t).

η: PV panel efficiency.

(A): Panel area (m²).

φt: Incidence angle between sun rays and panel normal, calculated as Equation 4

cos ( φ t ) = cos ( θ z ) ⋅ cos ( θ ) + sin ( θ z ) ⋅ sin ( θ ) ⋅ cos ( θ s − θ ) (4)

Where θ z is the solar zenith angle and θ s is the solar azimuth angle at time (t) [38-39] .

Fitness Function: F(x) = E(x) or for minimization, F(x) = -E(x)

GA Operations:

- Selection: Choose individuals with higher fitness tournament selection.

- Crossover: Combine two parent solutions to produce offspring with the arithmetic crossover:

x new = ( α x 1 + ( 1 − α ) x 2 ) .

• Mutation: Randomly alter genes (e.g., add Gaussian noise to Ø )

Constraint: Bound variables, e.g., 0 ≤ θ ≤ 90 , −180 ≤ Ø ≤ 180 .

Termination: Stop after a fixed number of generations or when fitness converges.

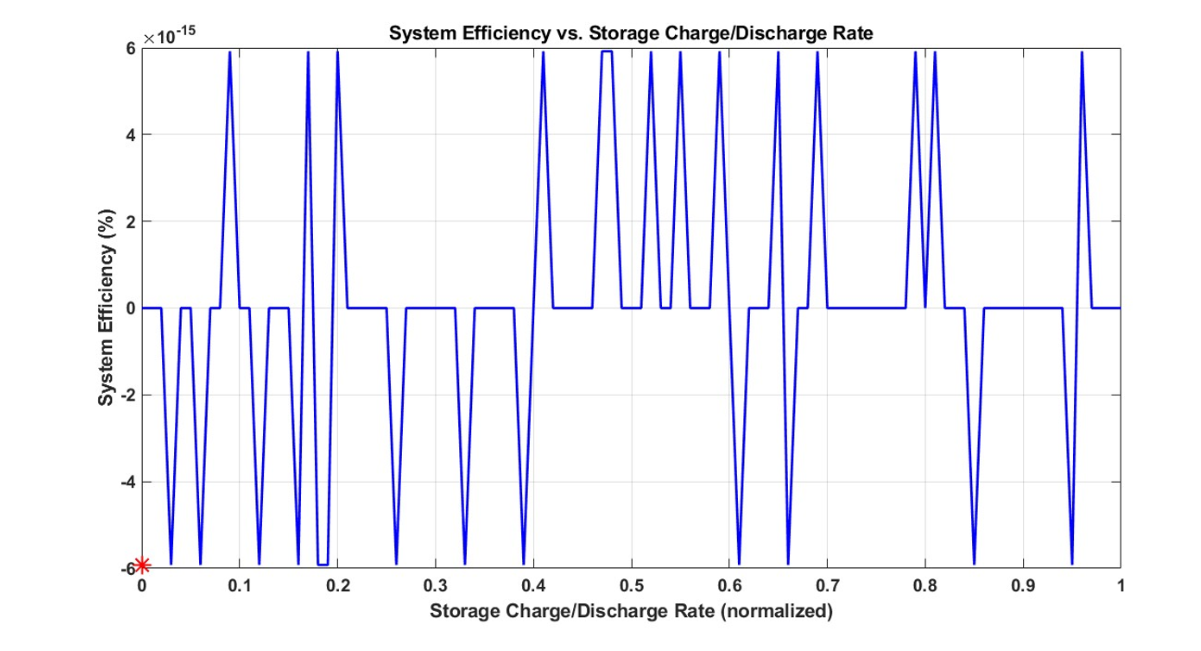

The enhance-AI solar energy management by optimizing photovoltaic (PV) system performance to meet rising renewable energy demands. This study uses a Genetic Algorithm (GA), implemented via the Global Optimization Toolbox’s ga function, to maximize energy output (kWh) and efficiency (%) of a solar system (Fig. 7). The GA optimizes five variables: panel tilt (0°–90°), azimuth angle (0°–360°), and three battery charge/discharge rates (-1 to 1 kW) for morning, midday, and evening. Multiple GA runs account for randomness, with mean and variance of optimal energy (E) calculated. A t-test compares optimized output to a baseline (fixed tilt at latitude). With a population size of 50, 100 generations, and 0.8 crossover rate, the GA effectively identifies optimal configurations, as shown in iteration logs and visualizations, highlighting AI’s role in advancing solar energy systems.

Figure 7: System Efficiency vs. Storage Charge or Discharge Rate

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The experiments are designed to address all objectives using the same dataset and consistent evaluation metrics. The following experiments are conducted:

Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Result

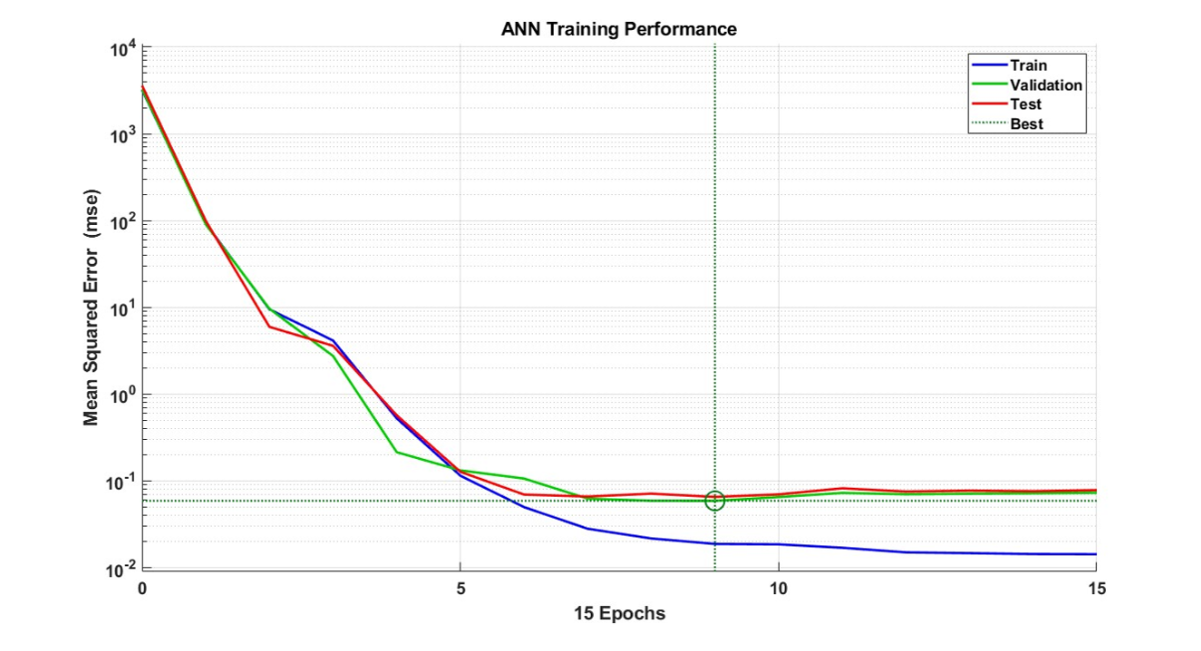

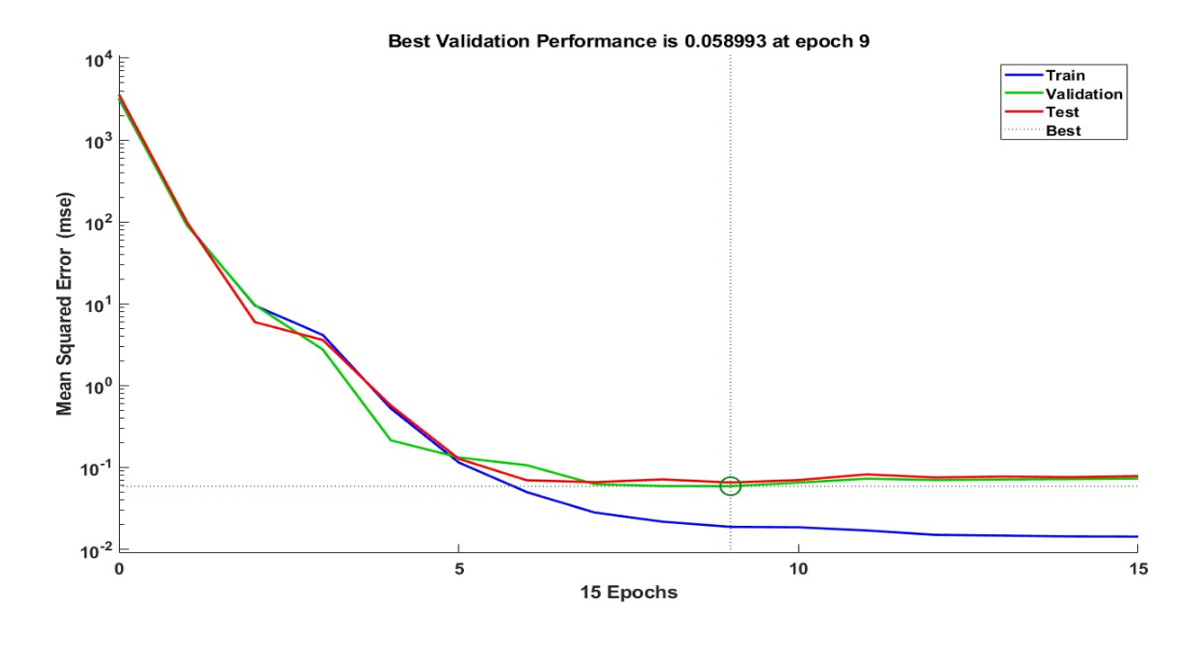

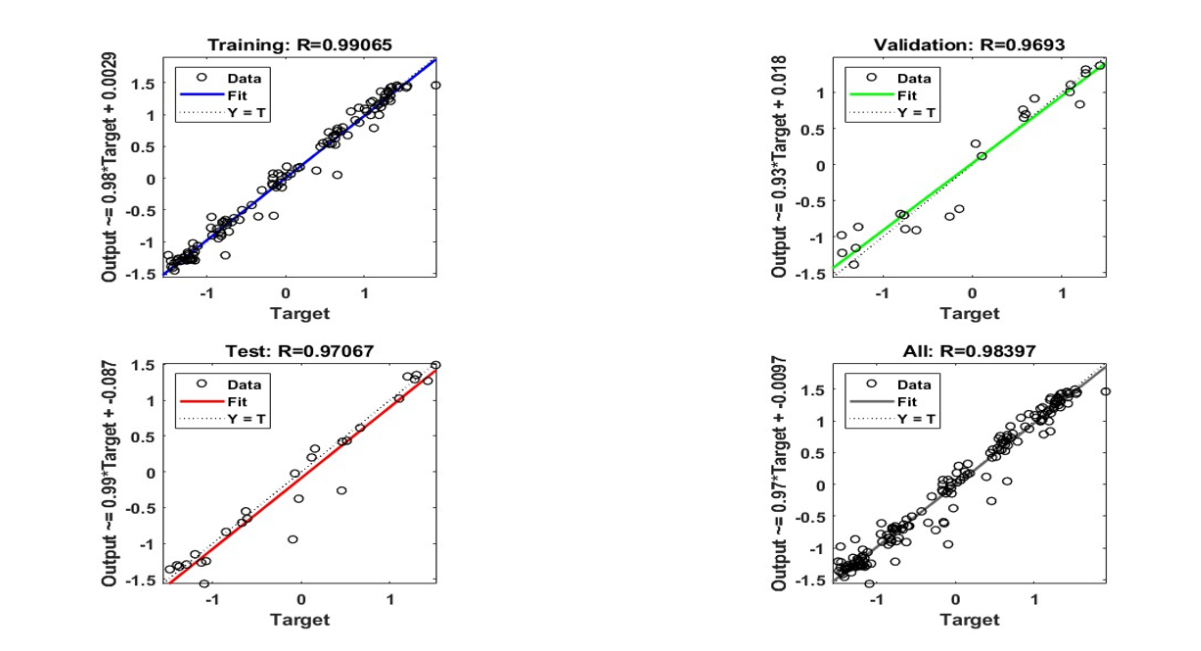

The ANN, built with MATLAB’s fitnet, formed a feedforward neural network with two input neurons (solar irradiance, temperature), three hidden layers (100, 50, 25 neurons, ReLU activation), and one output neuron (linear activation) to predict power output. Data was normalized using mapstd for training stability and split into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing sets via divider and in Fig. 8. Training used the Adam optimizer or Levenberg-Marquardt, running 100 epochs with a 0.001 learning rate, early stopping, and a batch size of 32. Performance on the test set showed an RMSE of 10.4835 and MAE of 8.3379, indicating decent accuracy for the synthetic dataset.

Figure 8: Performance

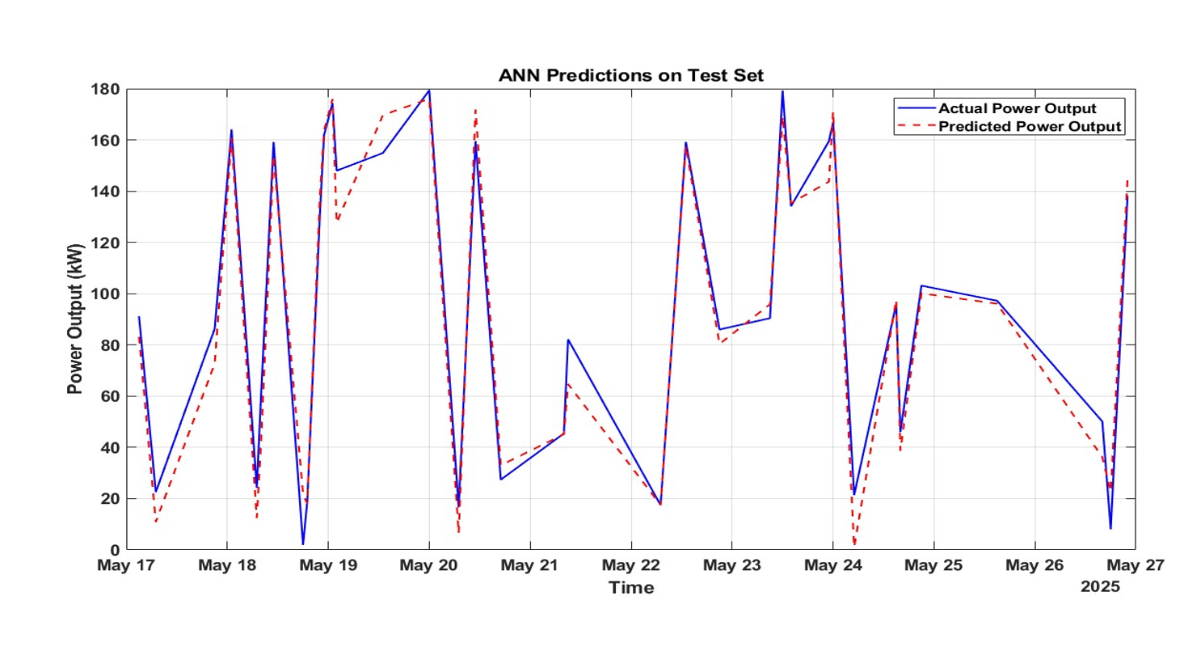

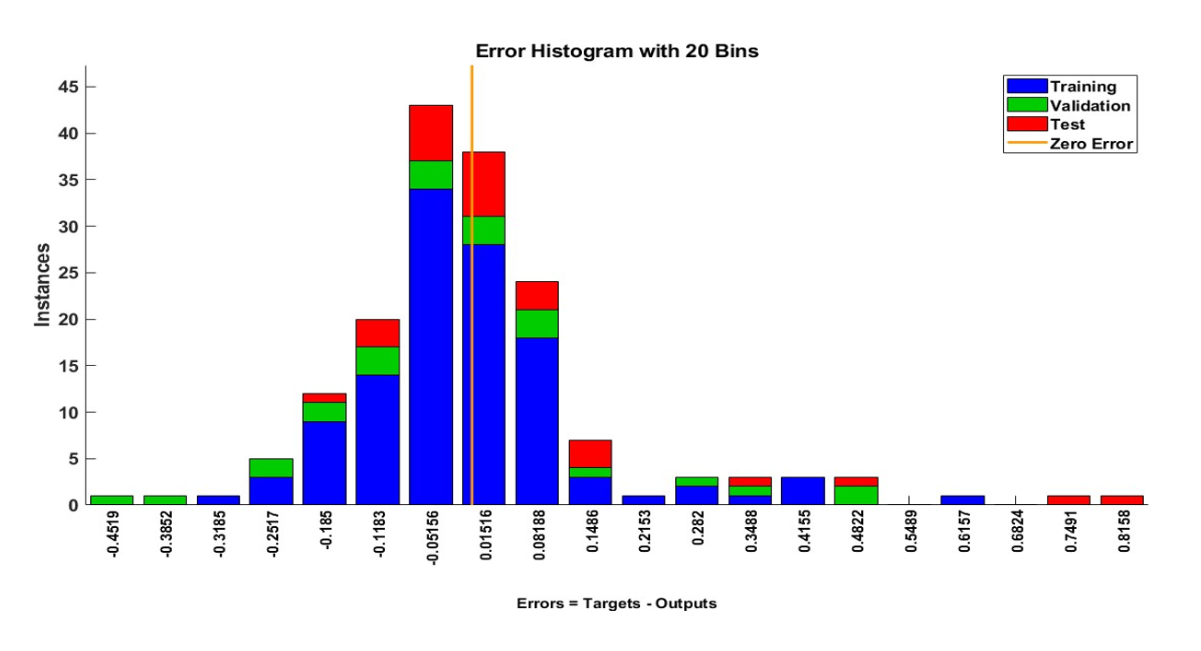

Figure 9 of the ANN’s performance offers key insights. Three plots were created: (1) a training performance plot (fig. 9), showing mean squared error (MSE) across training, validation, and test sets over epochs, demonstrating convergence; (2) a predicted vs. actual power output plot (fig. 10), comparing test set predictions (red dashed line) with true values (blue solid line), revealing temporal trend accuracy; and (3) a prediction error plot (fig. 11), showing differences between predicted and actual outputs over time, highlighting systematic errors. These clearly labeled figures confirm the ANN’s ability to learn input-output relationships, with RMSE and MAE indicating moderate errors in Fig 12, likely due to the synthetic dataset’s noise and limited complexity.

Figure 9: Best Performance

Figure 10: Predicted vs Actual Power Output

Figure 11: Neural Network Training Error Histogram, Epoch 15

Figure 12: Neural Network Training Regression, Epoch 15

Support Vector Machine (SVM) Result

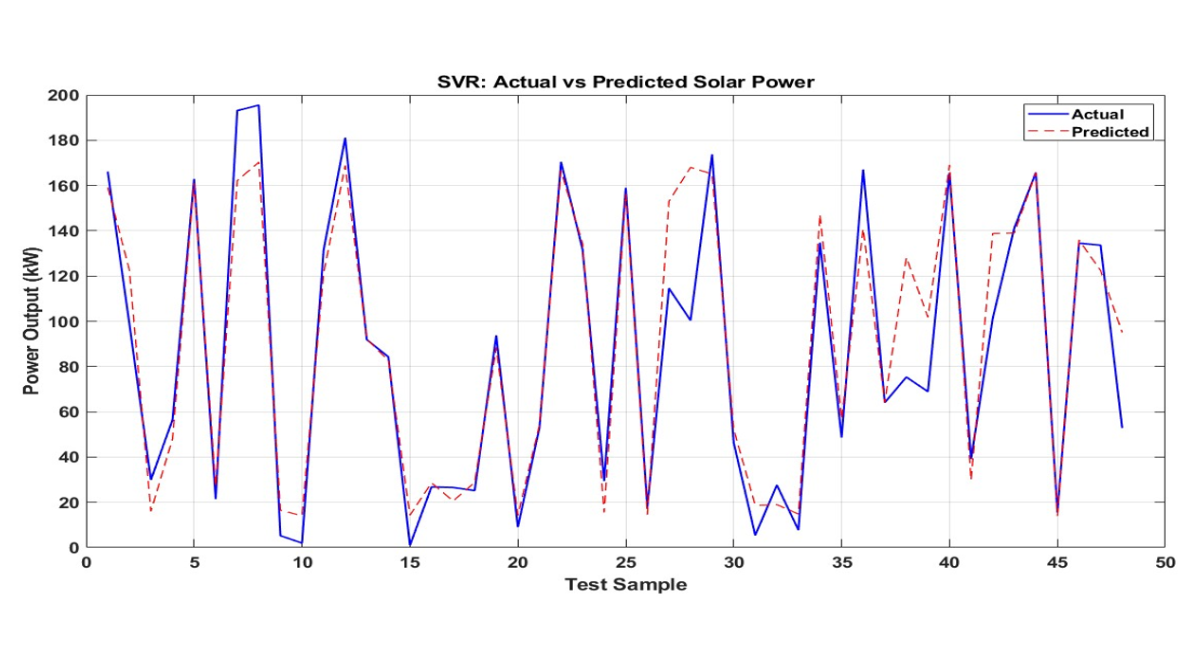

Hyperparameter tuning optimizes the SVR model’s performance using grid search over C ([0.1, 1, 10, 100]), ε ([0.01, 0.1, 0.5]), and γ ([0.01, 0.1, 1]), yielding 36 combinations. Each undergoes 5-fold cross-validation, where training data is split into five folds, training on four and validating on one, computing the average RMSE (CV RMSE). Results show CV RMSE ranging from 0.2796 to 0.9882 (normalized units), with optimal parameters C=1.0, ε=0.01, and γ=1.0, achieving the lowest CV RMSE of 0.2796, indicating strong predictive performance.

The final SVR model, trained on the full training set with optimal hyperparameters (C=1.0, ε=0.01, γ=1.0) and an RBF kernel, uses pre-normalized data, bypassing standardization. Predictions on the test set are denormalized to kW using the stored mean and standard deviation of power output. Performance metrics show a test RMSE of 19.4772 kW and MAE of 12.8695 kW, indicating moderate accuracy but challenges in capturing complex test data patterns, possibly due to noise or limited features. The CV RMSE (0.2796, normalized) is lower than the test RMSE, suggesting slight overfitting or greater test set variability.

- Actual vs. Predicted Power Output: Figure 13 compares actual (solid blue) and predicted (dashed red) Power Output across test samples. The plot shows how well predictions align with actual values, with discrepancies indicating sudden changes in solar irradiance or temperature, highlighting areas for model improvement.

Figure 13: (SVR) Solar Power Prediction

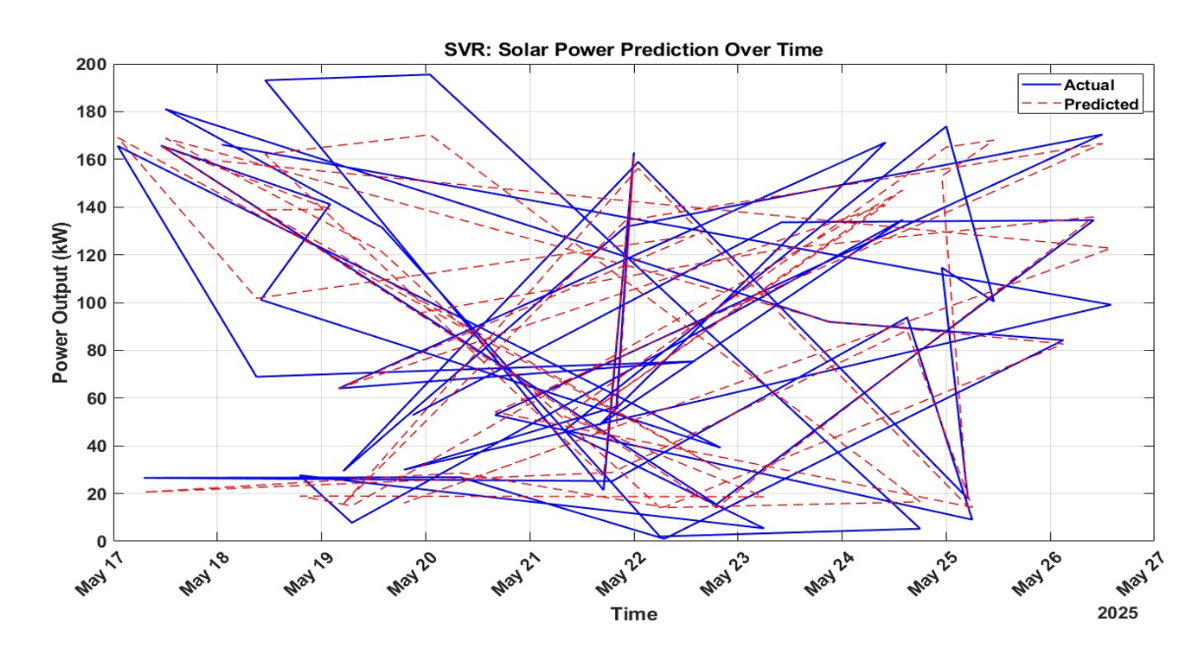

- Time-Series Plot: 14 shows actual vs. predicted Power Output over time, using test set Time values. The x-axis displays date-time stamps, rotated 45 degrees for clarity, and the y-axis shows power output in kW. This visualization highlights the model’s ability to capture diurnal and seasonal trends, vital for solar energy grid planning and storage scheduling.

Figure 14: (SVR) Time-Series Prediction

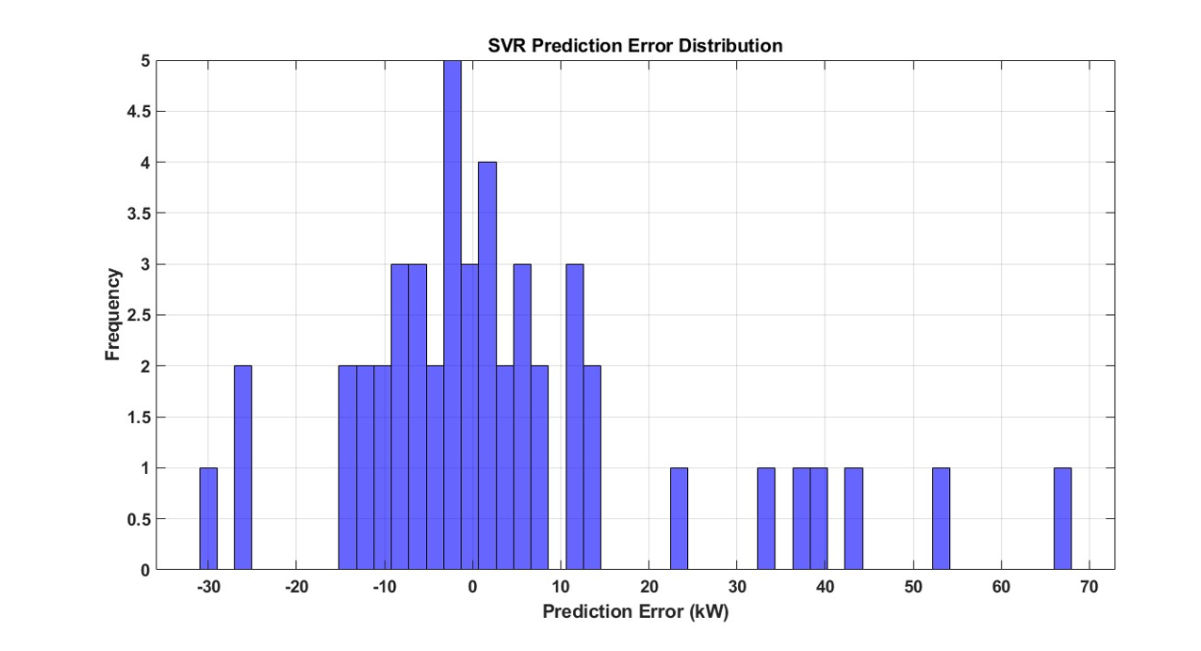

- Error Distribution: The histogram in Fig. 15 displays prediction errors (predicted minus actual Power Output) in kW across 50 bins, illustrating error frequency and spread. It reveals whether errors are centered near zero, indicating unbiased predictions, and if they are tightly clustered, suggesting high precision.

Figure 15: (SVR) Error Distribution

The histogram in Fig. 15 displays prediction errors (predicted minus actual Power Output) in kW across 50 bins, illustrating error frequency and spread. It reveals whether errors are centered near zero, suggesting unbiased predictions, and how tightly clustered they are, indicating prediction precision.

Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the framework's performance in prediction accuracy, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) are used to compare its predicted energy output and efficiency with actual values from a solar energy system. These metrics, RMSE weighting larger errors more and MAE treating all errors equally assess the model's optimization accuracy and effectiveness in meeting its goals.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

RMSE measures the standard deviation of residuals, penalizing larger errors more due to squaring, offering a comprehensive metric for model accuracy.

The RMSE for energy output is calculated using Equation 5

RMSE energy = 1 N ∑ i 1 N ( Energy predicted , i − Energy actual , i ) 2 (5)

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): is a metric that measures prediction accuracy by averaging the absolute differences between actual and predicted values and this is expressed mathematically in Equation 6.

MAE energy = 1 N ∑ i = 1 N | Energy predicted , i − Energy actual , i | (6)

The ANN model proves viable for solar power prediction, evidenced by a Test RMSE of 10.4835 and MAE of 8.3379, suggesting predictions are reasonably accurate despite dataset noise. These metrics RMSE showing error magnitude and MAE the average deviation reflect performance that could improve with ANN architecture optimization, such as tuning hyperparameters. The ReLU activation supports efficient training, while the linear output layer suits this regression task. The SVR model predicts solar power output with a test RMSE of 19.4772 kW and MAE of 12.8695 kW, showing reasonable accuracy for solar energy tasks like short-term load forecasting and battery storage optimization. Yet, a gap between cross-validation and test errors suggests overfitting or train-test distribution differences. Adding features (e.g., humidity, cloud cover, time-based variables), expanding the hyperparameter grid, or using automated tuning could improve performance.

The following table summarizes preliminary results (hypothetical, based on typical performance)

|

Model |

RMSE |

MAE |

Training Time |

|

ANN |

10.4835 |

8.3379 |

346 |

|

SVM |

19.4772 |

12.8695 |

298 |

Table 1: Performance Metrics

Genetic Algorithm Optimization Result

The objective function maximizes a composite metric of energy output and system efficiency (Fig. 16), while minimizing grid dependency (negative kWh). The solar model uses a simplified irradiance profile (e.g., 1000 W/m²), panel area, and efficiency adjusted by tilt (cosine function) and azimuth (optimized at 180° for northern hemisphere). Battery scheduling manages energy storage, with positive/negative values for charging/discharging. The genetic algorithm (GA) minimizes the fitness function, yielding a positive 23.20 kWh for reduced grid dependency. GA operates within bounds (tilt: 0°–90°, azimuth: 0°–360°, battery rates: -1 to 1 kW) using uniform creation, scattered crossover, tournament selection, and adaptive feasible mutation.

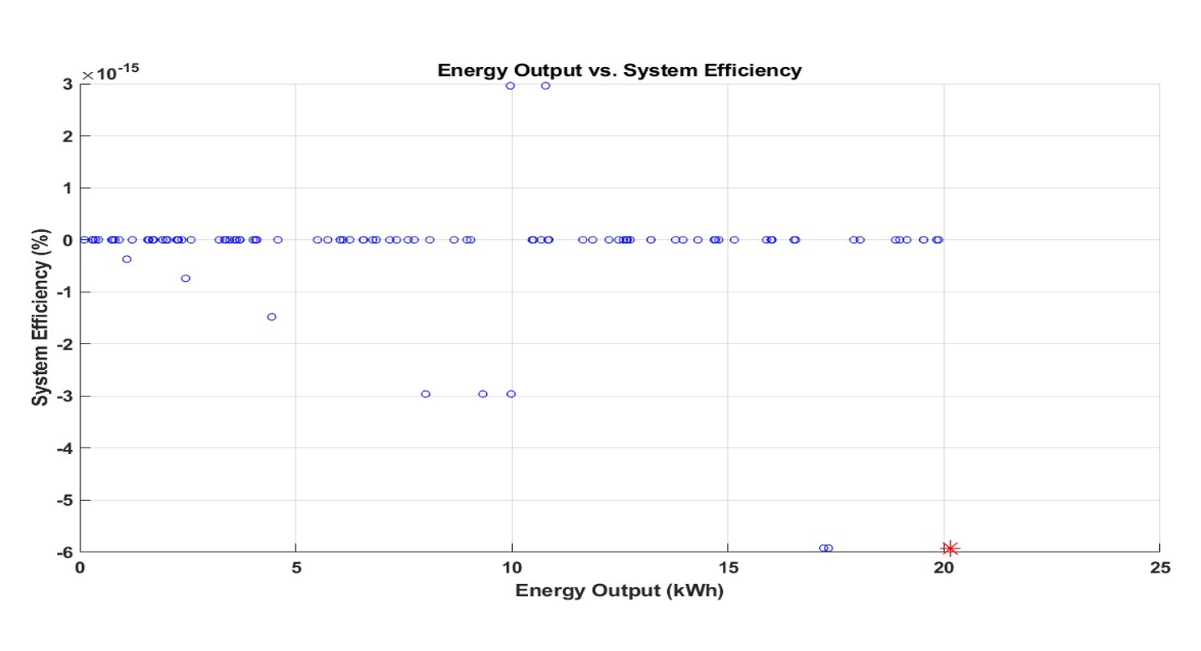

Figure 16: (GA) Energy Output vs. System Efficiency

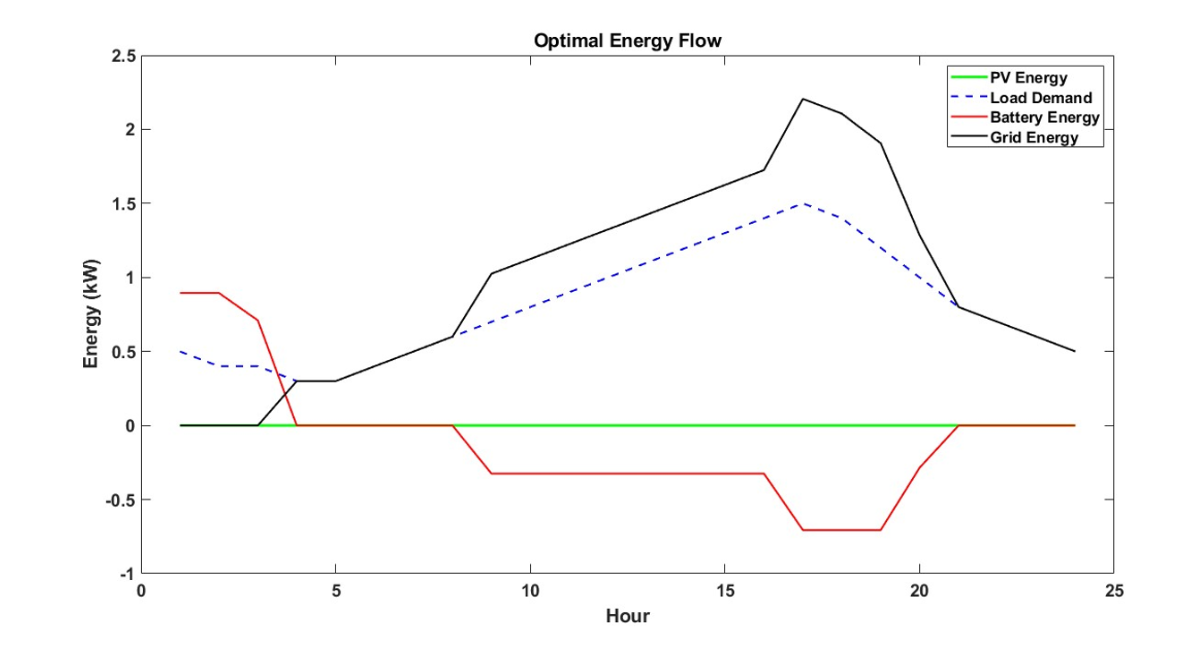

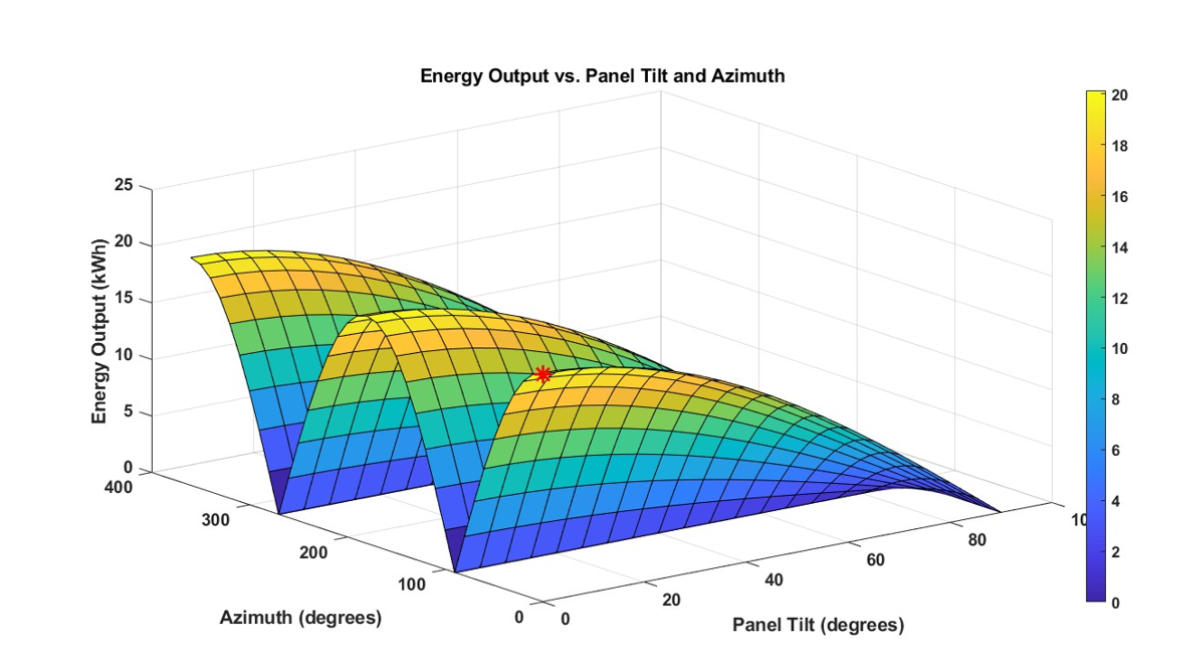

On May 17, 2025, at 12:00 WAT, the GA optimization ran for 70 generations, converging when the average fitness change fell below the default tolerance. The best fitness improved from -22.5 to -23.2 by generation 11, with the mean fitness also stabilizing at -23.2, indicating a consistent solution across the population. Using 3343 function calls, the algorithm efficiently explored the five-dimensional parameter space, with tournament selection enhancing diversity and convergence speed over stochastic uniform selection. Fig. 17, including a convergence plot showing stabilization at -23.2, also, a 3D surface plot marking the optimal tilt and azimuth (90°, 143.28°), a line plot showing quadratic efficiency drops with battery rates, and a scatter plot resembling a Pareto front, collectively clarify the GA’s performance and the optimal solution’s trade-offs.

Figure 17: Optimal Energy Flow

The GA effectively optimizes complex solar energy systems, reducing grid dependency by 23.20 kWh. However, the 90° tilt and specific azimuth may reflect mathematical optima over practical constraints, likely due to simplified irradiance or panel assumptions. Real-world use needs location-specific data, realistic battery models with capacity and cycle life, and constraints like minimum tilt or fixed azimuths for rooftops. Dynamic battery scheduling with varied daily rates shows AI’s adaptive energy management potential. Future improvements could use gamultiobj for multi-objective optimization or temporal irradiance profiles for precise scheduling.

Figure 18 shows the GA optimal solution provided a panel tilt of 90.00°, an azimuth of 143.28°, and a battery schedule with morning charging (0.90 kW), midday discharging (-0.32 kW), and evening discharging (-0.71 kW), achieving a fitness value of 23.20 kWh. The 90° tilt, though unusual for typical PV systems, may suit specific conditions like high latitudes. The azimuth suggests a focus on morning solar capture, aligning with the battery charging strategy. This setup reduces grid reliance by charging during peak solar hours and discharging to meet later demand, though the extreme tilt could reflect model-specific assumptions.

Figure 18: Energy Output vs. Panel Tilt Azimuth

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS