ABSTRACT

The present cross-sectional observational study sought to examine disparities in the intensity and frequency of micro-emotional expressions — specifically Action Unit (AU)12 (smiling, index of social engagement) and AU45 (blinking, index of sensory sensitivity) between autistic and Neurotypical children during naturalistic, unstructured free-play interactions, highlighting an urgent gap in existing literature that predominantly relies on controlled clinical environments such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). Using convenient sampling methods, 18 age- and gender-matched children (8 autistic: mean age 8.4 years, SD = 2.7; 10 Neurotypical: mean age 8.2 years, SD = 2.5) were selected from a larger cohort study.

Open Face 2.0 along with the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) was used to computationally analyse ten-minute free-play video recordings to derive AU frequency (occurrences per session) and intensity (0–5 scale). No statistically significant variations between groups were detected using independent samples t-tests: AU12 intensity (autistic M = 0.55 ± 0.32, Neurotypical M = 0.75 ± 0.43; t(16) = 1.092, p = 0.291), AU12 frequency (autistic M = 267.8 ± 115.0, Neurotypical M = 302.8 ± 150.0; t(16) = −1.284, p = 0.217), and AU45 intensity (autistic M = 0.85 ± 0). Promising trends were indicated by moderate effect sizes (Cohen's d = −0.266 for AU12 frequency and d = −0.609 for AU45 frequency). AU12 and AU45 frequencies showed a significant positive connection across groups (r = 0.821, p < 0.01), indicating entwined social-sensory processing patterns. The results obtained indicate interpersonal variations in spontaneous emotional expressiveness in empirically relevant naturalistic situations could potentially be modest or extremely context-dependent, as opposed to consistently defined. Prospective studies ought to emphasize larger samples and multimodal approaches (e.g., physiological arousal metrics) to recognise complex behavioural trends and guide personalized, neurodiversity-affirming interventions for autistic children aiming at real-world interpersonal participation and sensory regulation without enforced Neurotypical norms of expressivity.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD); Emotional Expressions; Action Units (AU); Open Face 2.0; Facial Action Coding System (FACS); Naturalistic Observations; Neurotypical; Social Interactions

INTRODUCTION

Background and Significance

Autism Spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by restricted and repetitive patterns of Behaviours, along with challenges with social communication and interaction [1]. ASD impacts 1 in 54 children and is associated with poorer outcomes in social, cognitive and adaptive functioning [2]. Reduced capacity to interpret and express emotions through typical social cues is seen in ASD and can have negative impacts on social communication and interpersonal relationships [3]. As sensitive markers of emotions that promote empathy and attachment, facial expressions are crucial for social communication in Neurotypical development [4].

Standardized techniques, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), are utilized extensively in research and therapeutic environments to assess these social and emotional abnormalities. ADOS offers organized environments for observing and evaluating certain social Behaviours in people with ASD, including gaze, emotional reciprocity, and facial expressiveness [5]. Multiple studies adopting ADOS indicates that children with ASD reveal less facial expression, less Eye contact, and a fewer number of emotional reactions than their Neurotypical peers. Face expressions, which are spontaneous in Neurotypical development, are generally less prevalent and less intense in children with ASD in these organized contexts, indicating variations in social motivation and affective processing [6]. Although ADOS covers key components of ASD-related social impairments, it might not adequately represent the unpredictable, impulsive emotional displays occurring during regular experiences [7].

This research seeks to fill these gaps by analyzing emotional expressions in free play contexts, going past traditional evaluations to record spontaneous, contextually rich interactions. This strategy offers an improved comprehension of emotional processing in ASD and establishes the foundation to construct actions that improve social engagement. Subsequently investigating the significance of facial expressions and action units in preserving the minute variations in emotional expressiveness in ASD.

Importance of Studying Emotional Expressions in Autism

Research consistently demonstrates people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) possess aberrant emotional expression patterns impacting social relationships, leading to misinterpretation and disengagement [3]. Autistic individual’s exhibit muted facial expressions along with reduced spontaneity, leading to increased social difficulties and solitude. ASD individuals may struggle to perceive and communicate social cues due to neurodevelopmental abnormalities [8].

The Facial Action Coding System (FACS) assists in measuring fundamental expressive variations by categorizing facial muscle movements into Action Units (AUs) [9]. AU12, related with the lip-corner puller (smiling), is of special significance in ASD research since it represents social comfort and positive emotion. AU45 (blinking) is frequently associated with enhanced sensory arousal, a common feature in ASD, wherein increased sensory sensitivity might affect social interaction and contribute to avoidance Behaviours in anticipation of excessive stimulation [10-11]. Greater AU45 activity suggests a possible adaptive response to higher sensory demands, whereas decreased AU12 activation is frequently seen in autistic children, indicating lesser spontaneous social interaction [12]. These AU traits enable us to recognise the sensory and social processing abnormalities that define ASD.

Recent meta-analyses (2021-2025) demonstrate ongoing impairments in facial emotion recognition and production in ASD across fundamental emotions, alongside specific task characteristics (e.g., dynamic vs. static, naturalistic vs. posed) significantly affecting variance magnitudes; dynamic and spontaneous stimuli frequently disclose heterogeneous patterns than monotonous ones. In genuine encounters, automated tools exhibit inconsistent group differences, with irregular timing, synchronization, or intensity rather than a total lack of emotions.

ASD research on emotional expression has typically employed standardized clinical paradigms, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), which is intended to provoke certain Behaviours in controlled settings [5]. Although useful, these uniform evaluations might disregard the spontaneity and diversity of emotional manifestations found in natural situations, where social interactions seem more fluid and unexpected [13]. Monitoring displays of emotion in unstructured, naturalistic contexts, including free play, could therefore give an improved ecological realistic perspective on the social issues that autistic people encounter. This method emphasizes the significance of investigating these relationships outside of therapeutic settings to better inform therapies that promote true social engagement.

Theoretical Framework: Emotional Processing in ASD

Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) display distinct patterns of emotional expression, generally characterized by aberrant facial expressivity, delayed reactions, and diminished emotional spontaneity [15]. Many previous investigations, however, used organized clinical examinations, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), to analyze these patterns [5]. Even though ADOS and comparable tools are essential for discovering fundamental interpersonal and emotional deficits, they usually restrict observations to established causes or responses, possibly restricting naturalistic expression of sentiments and insights into spontaneous social Behaviours in daily life [13].

The inability to capture unedited emotional reactions indicates a fundamental shortcoming in existing ASD research approaches. The variations evaluation of feelings expressed in naturalistic settings possesses an opportunity to identify subtle aspects of interaction with others and perception that are context-specific and are likely to appear in less constrained, real-world interactions [6,16]. Monitoring children with ASD in unstructured play environments, for example, can demonstrate how micro-emotional expressions, such as subtle smiles (AU12) or frequent blinking (AU45), act as signs of emotional and sensory processing states providing an insight into feelings of security, social engagement, or sensory overload, which may be tricky to detect in structured settings [3,17].

Open Face 2.0 and FACS are implemented for this study to quantitatively measure AU12 and AU45 in a free play setting. The particular action units were specified as they are pertinent to ASD-related Behaviours; AU12, associated with smiling, illustrates social comfort and engagement, whereas AU45, linked with blinking, corresponds to sensory arousal and vigilance, both of which are considered atypical in ASD [4,10].

Refined social motivation frameworks (2022-2025) highlight variation in ASD social reward processing, with anxiety and sensory overload acting as significant modulator of expressivity. Naturalistic paradigms utilizing automated FACS/Open Face demonstrate that emotional expressiveness variations are frequently context-specific, with decreased social attentiveness or synchronization rather than universal muting. The investigation applies unstructured observational information to investigate differential patterns of expression among autistic and Neurotypical children, in the objective of resulting in perspectives that proceed beyond outcomes from structured clinical assessments [11-12].

Current Gaps in Research

A substantial amount of present study is centered on evaluating emotional expression in ASD within controlled settings, mainly through instruments including the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), a standardized clinical instrument that seeks to induce specific social Behaviours [5]. Whereas ADOS has proven useful in determining wide the emotional and social development deficits in ASD, it solely records a narrow spectrum of Behaviours within structured contexts, likely ignoring the flexibility and spontaneity that characterize social interactions in real life [5,7]. ADOS's organized nature may unintentionally limit the range of emotional displays since these circumstances lack the flexibility of genuine social contexts where social signals vary on their own.

This quantitative limitation results in a significant lack of understanding about autistic children's emotional expressions in standard contexts, especially during uncontrolled social interactions enabling for authentic, adaptable emotional displays. Investigating emotional expressions in unstructured situations, like as free play, could provide a ecologically sound understanding of social functioning in ASD [13].

Problem Statement and Study Scope

The excessive reliance on standardized clinical paradigms (such as ADOS), limit spontaneous Behaviours, diminish ecological validity, and possibly unintentionally overestimate the severity and consistency of emotional expressivity deficits, is a prevalent challenge in the literature currently available on emotional expression in autism spectrum disorder. As a result, there remains an inadequate amount of information of how autistic children adopt micro-emotional expressions in ordinary, unstructured social encounters wherein spatial adaptability enables the development of real and changeable sensory-social dynamics. The research initiative focuses on spontaneous micro-expressions (AU12 and AU45) throughout 10-minute free-play sessions in middle childhood (ages 6-11 years), prioritising real-world authenticity over controlled stimulation to provide additional generalizable approaches.

Study Objectives, Research Questions and Hypotheses

The primary objective of the present research intended to use automated FACS/Open Face analysis to compare the frequency and intensity of Action Units AU12 (social engagement via smiling) and AU45 (sensory sensitivity via blinking) in autistic and Neurotypical young children during naturalistic free play interactions.

Concrete aims:

1) Comparing group-specific means and effect sizes on AU12 and AU45 metrics to Neurotypical children.

2) Examine correlations between AU12 and AU45 as markers of potential social-sensory interplay; and

3) To analyse our results for the construction of ecologically justified and personalised interventions in ASD.

Research Question 1:

How do autistic and Neurotypical children differ in the frequency and intensity of Action Units during free play, specifically AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking)?

This enquiry examines if autistic children's spontaneous social expressions differ from those of Neurotypical children. It focuses on AU12 and AU45 as measures of social comfort and sensory sensitivity, respectively.

Research Question 2:

What distinct patterns of emotional expression, represented by combinations of AUs, are more prevalent in autistic children compared to Neurotypical controls?

This area attempts to examine if autistic children demonstrate distinctive patterns of AU combinations, which may act as indications of social engagement or disengagement particular to ASD in naturalistic contexts.

Hypothesis 1:

Autistic children would exhibit considerably reduced frequency and intensity of AU12 (smiling) than Neurotypical children, consistent with evidence demonstrating diminished spontaneous social interaction in ASD (Jones et al., 2020). This lowered AU12 activation is likely to represent decreased ease in unstructured social contexts.

Hypothesis 2:

Autistic children will experience higher frequency and intensity of AU45 (blinking) than Neurotypical children, suggesting enhanced sensory activation or alertness, consistent with previous results demonstrating higher sensory sensitivity in ASD [10-11].

Hypothesis 3:

When contrasted with Neurotypical controls, autistic children would exhibit unusual patterns in AU combinations, particularly those involving AU12 and AU45, reflecting atypical reactions to free play social interactions.

New meta-analyses and systematic reviews (2021-2025) consistently indicate deficiencies in facial emotion detection reliability and rapidity in ASD, with significant effect sizes for fundamental emotions; however, production (spontaneous expression) represents a stronger variable. Mechanical FACS-based research in naturalistic or semi-naturalistic situations (2024-2025) suggests that variations are prone to present as irregular schedules, poorer synchronisation with social partners, or modest intensity alterations than outright absence. In this regard, evidence-based studies utilising mobile FER during ADOS segments supports the viability of identifying smiles (AU6+AU12) but underlines difficulties in realistic situations (movement, occlusion, subtlety).

Sensory features, particularly blinking (AU45), are understudied in spontaneous situations; new investigations (2020-2025) confirm abnormal sensory processing as central to ASD, with hyper-reactivity being connected to internalizing/externalizing issues Robertson & Simmons, 2018 update; 2023 blink rate studies. Although distinctions between groups are inconsistent in unstructured contexts, excessive blinking may be an adaptive coping technique for visual/auditory overload during social play.

Out-of-the-box observation: Naturalistic data reveals dynamic interaction (e.g., social engagement traded against sensory control), supporting substantial AU12–AU45 correlations here despite non-significant means; excessive emphasis on organised tasks might trigger an artefact where impairments look more discrete. This highlights the importance of multimodal, longitudinal approaches in capturing variability and informing neurodiversity-affirming services.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional observational research evaluated the emotional displays of autistic and Neurotypical children during realistic social interactions. The study comprised 18 children: 10 Neurotypical children (mean age = 8.2 years, SD = 2.5) and 8 autistic children (mean age = 8.4 years, SD = 2.7) as shown in the table 1. Participants were matched by age and gender to reduce variability due to developmental or demographic variables, ensuring that the focus remained on variations in emotional expression patterns particular to ASD.

The ADOS-2 evaluation, which was verified by licenced clinical psychologists, confirmed all autistic individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. To ensure sample uniformity children with other neurological disorders that potentially affect emotional expressiveness were eliminated [18]. Participants were recruited at first for more extensive research on social and emotional behaviours in a variety of settings. For this research, we looked at a 10-minute portion of free play video footage collected among each participant and an assessor to capture spontaneous emotional reactions of children in an unstructured situation.

The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee examined and approved the study protocol (REF: 2013/502 and 2013/341). Carers gave informed consent before participating.

|

Group |

Number of Participants |

Mean Age (years) |

Standard Deviation (SD) |

Gender Distribution (M/F) |

|

Neurotypical |

10 |

8.2 |

2.5 |

5/4 |

|

Autistic |

8 |

8.4 |

2.7 |

4/4 |

|

Total |

18 |

Table 1: Participant Characteristics

Tools and Materials

Video Recording System

High-resolution digital cameras were employed for recording each session and capture participants' facial expressions in a genuine social context. Video recordings were made of 10-minute free play interactions between children and assessors, which were set up at eye level to achieve the best face visibility. This system sought to maximise data dependability by capturing spontaneous, unstructured encounters in real time, offering a wealth of information for analysing subtle emotional signals.

Facial Action Coding System (FACS) and Selection of Action Units (AUs)

Ekman and Friesen (1978) developed the Facial Action Coding System (FACS), providing a framework for categorising facial expressions into Action Units (AUs), each of corresponding to distinct muscle movements. FACS facilitates the exact, objective examination of complex emotional expressions, which are frequently unusual in people with ASD, hence assisting in the capture of subtle social and sensory impairments.

The present research focuses on AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking) as these have previously been demonstrated to be associated with social interaction and sensory sensitivity. AU12, which represents the lip-corner puller, is often seen as a sign of social friendliness and involvement. Autistic children frequently exhibit less frequent and lower-intensity AU12, which corresponds to known disparities in spontaneous social interactions. In contrast, AU45, which includes blinking, measures sensory sensitivity and alertness areas whereby individuals with ASD frequently display heightened responsiveness, particularly in novel or unstructured contexts [11]. Therefore, using AU12 and AU45 allows for a two-dimensional analysis focusing on both interaction with others and sensory arousal in a realistic context, which aligns with the study's goal of capturing distinctive emotional patterns in ASD.

This investigation focuses on AU12 and AU45 pairings to examine trends in engagement and sensory reactivity in free play, addressing a gap created by prior ASD studies that used FACS in organised clinical settings. Recent ASD research suggests that using FACS in a naturalistic setting, such as free play, improves ecological validity and captures a more realistic variety of emotions [13]. This technique builds on the necessity for observational approaches that mirror real-world encounters in which emotional expressions may arise spontaneously instead of in response to scripted cues.

Open Face 2.0

Open Face 2.0 is a breakthrough forward in computational facial analysis, with substantial capabilities for recording small, dynamic facial movements that are crucial to ASD research in realistic situations. The Convolutional Experts Constrained Local Models (CE-CLM) deep learning technique is applied in this application to precisely record real-time changes in Action Units (AUs) that have excellent resiliency to environmental factors like movement, angle, and lighting variations. This is crucial for preserving the integrity of the data during unstructured free play sessions [14].

For ASD-specific investigations, Open Face's capacity to gather evidence at such granularity outperforms previous techniques that depended on laborious frame-by-frame FACS coding that was unsuitable for unstructured social environments. Furthermore, subsequent research has confirmed Open Face 2.0's excellent fidelity in detecting ASD-specific AUs, giving critical quantitative data to expand improve our understanding of social relationships and sensory processing in autistic children.

Data Collection and Processing

Each session was captured with high-resolution digital cameras placed at face level to enable clear images of the children's facial expressions, which is required for AU analysis [10]. The 10-minute sessions involved children in free play activities meant to elicit spontaneous emotional reactions, which is consistent with recent results on the benefits of unstructured interactions for researching ASD-related expressiveness [12]. Open Face 2.0 was used to analyse video material and extract AUs such as AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking), providing quantitative estimates of frequency and intensity [10,14].

Considering the unpredictable quality of free play, data reliability and precision required preprocessing. The pre-trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model in OpenFace 2.0 provides normalisation against illumination and movement fluctuations, addressing common issues in realistic situations [19]. Frame-by-frame analysis enabled exact AU data extraction, with pretreatment procedures for head alignment and gaze modification to account for natural orientation variations, increasing measurement reliability. To assure the validity of collected emotions, AUs particular to the children were separated, avoiding superfluous contributions from those not present.

To improve reliability of comparing AU intensity among children, median AU scores per participant were removed from individual frame data [14]. This thorough cleaning was critical in obtaining an ecologically valid dataset that properly portrayed each child's actual manifestations of social engagement and sensory response in an unstructured situation.

Variables and Outcome Measures

Frequency and Intensity of Action Units

The primary outcome variables in this research were the frequency and intensity of AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking), evaluated in children while playing. Frequency, defined as the quantity of occurrences of each AU per unit of time, demonstrates how frequently each expression was witnessed, while intensity was measured on a scale of 0 to 5, representing the degree of muscle activity, as categorised by Ekman and Friesen (1978). Open Face 2.0 distinguishes five intensity levels: trace, minor, prominent, severe, and maximum, which corresponds to gradual increases in emotional expressiveness [20]. The significance of AU12 and AU45 in ASD studies has been demonstrated by earlier research, such as Goodwin, that attributes them to enhanced sensory sensitivity and positive social interaction, respectively [12].

This approach captures subtle and prominent facial emotions, allowing for a more thorough investigation of facial behaviours in ASD and Neurotypical populations [10,14].

Statistical Analysis

Independent samples t-tests were used to compare the frequency and intensity of AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking) in free play sessions between autistic and Neurotypical children. These t-tests resolve Aim 1 by contrasting the Action Unit groups individually. Cohen's d effect sizes were also presented, with thresholds of 0.2 (small), 0.5 (moderate), and 0.8 (big) to reflect the findings' practical importance.

For Aim 2, which investigates specific patterns of AU combinations, logistic regression was performed to evaluate whether the combined frequency and intensity of AU12 and AU45 could consistently categorise subjects as autistic or Neurotypical. This study investigates whether interaction patterns between AU12 and AU45 serve as indications of ASD-specific expressiveness.

Supplementary Pearson and Spearman's correlations were employed to examine the associations among the frequency and intensity of AU12 and AU45 within each group, offering insight into how social and sensory indicators might vary in autistic vs Neurotypical children [3,12]. SPSS version 26 was used to conduct all statistical tests, with a significance level of p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Methodological Considerations

The study's usage of Open Face 2.0 in a free play context constitutes a methodological breakthrough in ASD research. Unlike traditional organised paradigms, this naturalistic method captures the complexity and diversity of spontaneous emotional displays, which improves ecological validity. The 360-degree recording device improves the data by collecting a comprehensive perspective of the children's interactions, giving a more complete context for understanding micro expressions in dynamic contexts [13].

Nevertheless, the limited number of samples is a constraint, which could have an impact on statistical power and generalizability. Furthermore, studying merely one unstructured session may not capture the entire spectrum of expressive behaviour across multiple circumstances. Future research should involve bigger, more varied samples and study other situations to corroborate the tendencies seen here, addressing concerns for robustness in generalizability [21].

RESULTS

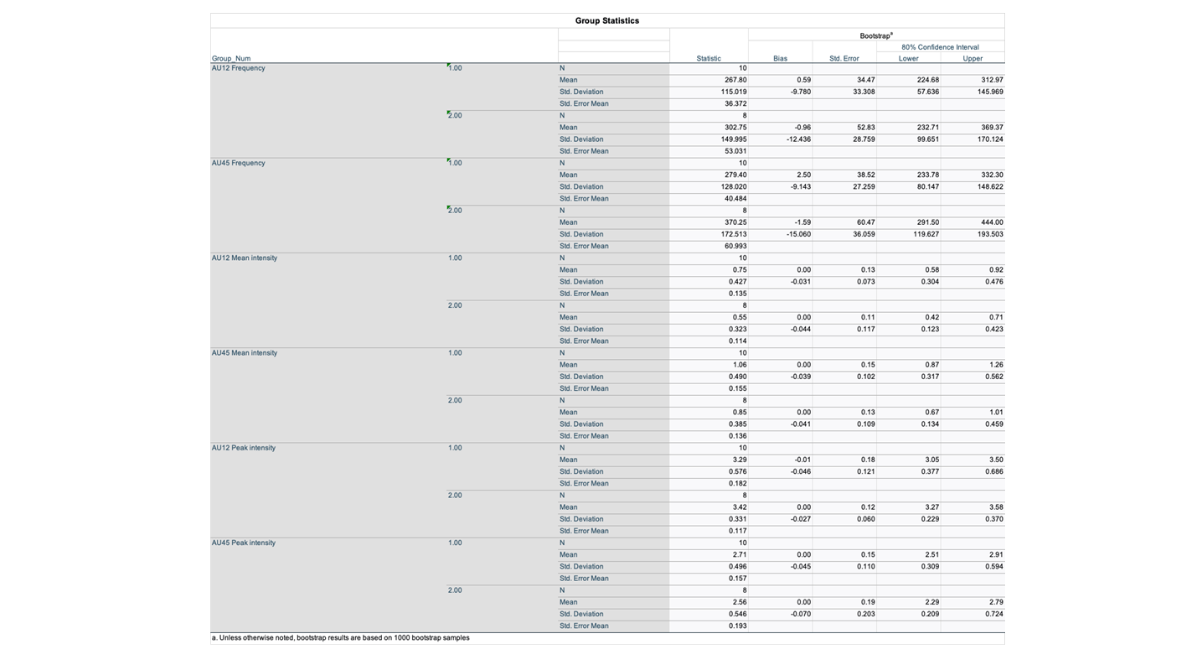

Descriptive statistics for observed action units in each group across the free play period are shown in Table 2. Independent samples t-tests indicated no statistically significant differences in frequency. Table 2 shows descriptive data for the observed Action Units (AUs) AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking) during free play. The autistic group reported a mean AU12 frequency of 267.8 (SD = 115.0), while the Neurotypical group showed a mean of 302.8 (SD = 150). The mean AU12 intensity in the autistic group was 0.55 (SD = 0.32), while the mean in the Neurotypical group was 0.75 (SD = 0.43). In terms of AU45, the autistic group had a mean frequency of 370.3 (SD = 172.5), as opposed to 279.4 (SD = 128.0) in the Neurotypical group, with mean intensities of 0.85 (SD = 0.39) and 1.06 (SD = 0.49), respectively.

Descriptive Statistics and Mean Differences

Table 2 provides an overview of the frequency and intensity for AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking) in both autistic and Neurotypical groups. Although there were variations in the means, t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences between the groups.

|

Action Unit (AU) |

Group |

Frequency (Mean ± SD) |

Intensity (Mean ± SD) |

|

AU12 (Smiling) |

Autistic |

267.8 ± 115.0 |

0.55 ± 0.32 |

|

Neurotypical |

302.8 ± 150.0 |

0.75 ± 0.43 |

|

|

AU45 (Blinking) |

Autistic |

370.3 ± 172.5 |

0.85 ± 0.39 |

|

Neurotypical |

279.4 ± 128.0 |

1.06 ± 0.49 |

Table 2: Mean and standard deviation for AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking) frequency and intensity in autistic and Neurotypical groups.

These descriptive findings demonstrate that, on average, autistic children exhibited somewhat lower AU12 frequency and intensity values than Neurotypical children, indicating a trend towards poorer social engagement; nevertheless, these differences were not significant. In contrast, the autistic group exhibited a greater frequency of AU45 (blinking), which corresponded to tendencies of increased sensory sensitivity documented in ASD literature, however this difference was not statistically significant.

Inferential Statistics and Non-Significant T-Tests

Independent samples t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences in the frequency or intensity of AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking) between the autistic and Neurotypical groups. The t-test results for AU12 frequency were −0.560, p = 0.583 (t(16)=−0.560,p=0.583), whereas AU12 intensity was 1.092, p = 0.291 (t(16)=1.092,p=0.291). This suggests that the variations in social expressiveness (AU12) were not statistically significant across the groups.

Similarly, AU45 (blinking) analyses revealed non-significant results: AU45 frequency (t(16)=−1.284,p=0.217) and intensity (t(16)=1.023,p=0.321) were both non-significant. These results indicate that sensory reactivity, as evaluated by blinking, did not differ substantially between autistic and Neurotypical children in our group.

These non-significant findings are consistent with the study's goal of investigating possible group differences; however they show no statistically significant variation in either social engagement (AU12) or sensory arousal (AU45), as measured by these Action Units.

Table 3: Bootstrap results based on 1000 Bootstrap Samples

Effect Sizes and Their Interpretation

Effect sizes were computed using Cohen's d and Hedges' correction for small sample bias to comprehend the distinctions between autistic and Neurotypical groups. The impact size for AU12 frequency was d=-0.266, showing a slight effect and a small decline in smiling frequency among autistic children in relation to Neurotypical peers, but not statistically significant. The impact size for AU45 frequency was -0.609, indicating a modest effect. This shows that autistic children may have a slightly greater blinking frequency, maybe due to sensory sensitivity. However, this result lacks statistical significance.

By providing impact sizes in our reporting, we give extra perspective to clarify the real-world significance of observed trends, even if they were not statistically significant changes.

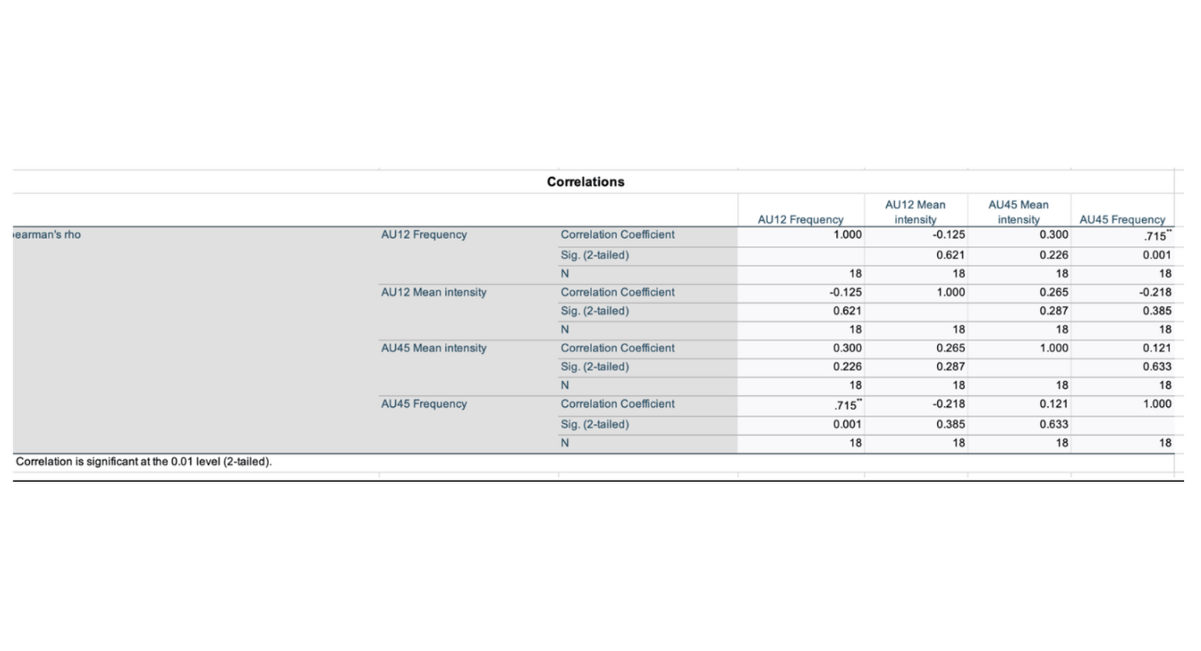

Correlation Analysis

Pearson's and Spearman's correlations were applied to investigate the link between social engagement (AU12) and sensory sensitivity (AU45). The purpose of this study was to determine if the display of social interaction through AU12 (smiling) was related to sensory arousal as evaluated by AU45 (blinking) in both autistic and Neurotypical groups. While this link does not directly relate to the major objectives, it could provide insights into potential interactions between social and sensory processing that may characterise the ASD phenotype in real-world circumstances.

The Pearson correlation revealed a strong positive association between AU12 and AU45 frequencies (r=0.821, p<0.01), suggesting that greater instances of social expressions (smiling) were correlated with higher blinking frequency, pointing to heightened sensory reactivity.

Spearman's rank correlation (ρ=0.715, p=0.001) confirmed the stability of the link across various statistical assumptions. These findings indicate a link among social and sensory processing that transcends group status, since both autistic and Neurotypical children showed a positive association between AU12 and AU45.

Although not essential to the study's primary goals, the strong link between AU12 and AU45 could serve as a foundation for future research into how sensory sensitivity may modulate social engagement behaviours in ASD, potentially influencing measures intended for enhancing social adjustment in sensory-rich environments.

Correlations

|

N |

18 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

|

|

AU45 Mean intensity |

Pearson Correlation |

0.191 |

0.159 |

1 |

-0.061 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0.447 |

0.529 |

0.809 |

||

|

N |

18 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

|

|

AU45 Frequency |

Pearson Correlation |

.821** |

-0.304 |

-0.061 |

1 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0 |

0.22 |

0.809 |

||

|

N |

18 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

Table 4a: Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Table 4b

Interpretation of Non-Significant Results and Future Directions

The dearth of significant distinctions between groups in AU12 and AU45 frequency and intensity implies that emotional expressiveness differences between autistic and Neurotypical children in naturalistic free play are minor. This emphasises the importance of bigger sample numbers or enhanced approaches for capturing possibly modest differences in ASD-related emotional expressions, which may be greater context-dependent and varied than previously thought.

DISCUSSIONS

The purpose of this study was to discover if autistic and Neurotypical children differed in their micro-expressions of AU12 (smiling) and AU45 (blinking) in a naturalistic, unstructured play setting, and if these differences provided insights into sensory and social processing in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Although there were no statistically significant differences, trends in the AU12 and AU45 measurements point to important areas for understanding autism's influence on spontaneous social behaviours and sensory response. These findings advance the research by highlighting the various ways in which ASD expresses itself in unstructured, ecologically valid situations.

Aim 1: Social Engagement via AU12 (Smiling)

The first objective aimed to examine at AU12 expression in autistic children, with the hypothesis that lower frequencies and intensities suggest less social interaction. Descriptive data corroborated this prediction, with autistic children smiling less frequently than their Neurotypical friends, consistent with findings of diminished spontaneous social interaction in autism [3,22]. Although these data were not statistically significant, they do imply that AU12 may still be used as a predictor of social comfort levels in ASD, particularly in unstructured environments where social expectations are less defined [23]. This suggests that AU12 might be utilised as an indication of spontaneous social interactions in real-world circumstances, increasing its use beyond planned evaluations.

Aim 2: Sensory Sensitivity via AU45 (Blinking)

The second objective was to identify AU45, which is related with blinking, as a measure of sensory arousal and reactivity. Autistic children had a greater frequency of AU45, which is consistent with previous research on sensory hypersensitivity in autism [11]. The rise in blink frequency detected in this study might be an adaptive method for regulating sensory overload in social interactions, a pattern seen in ASD as a reaction to increased environmental stimuli. This information suggests that AU45 is useful as a behavioural marker for sensory processing abnormalities in autism, emphasising the intricate interaction between sensory and social systems in unstructured situations [10].

Alternative Interpretations and Contextual Considerations

Although AU12 and AU45 trends supported the study's conclusions, additional reasons should be considered. A possible theory is that autistic children might value sensory input above social involvement in unfamiliar surroundings, perhaps resulting in diminished social responses such as smiling as an adaptive coping technique. This is consistent with the diverging social motivation hypothesis, which proposes that autistic children may prioritise sensory over social participation in overstimulating situations [22]. Furthermore, external variables such as environmental noise and unfamiliar social dynamics may amplify this trend, implying that future studies ought to look at physiological measures such as heart rate variability in addition to AUs to get a more comprehensive picture of sensory-social interactions [24-25].

Future Directions and Broader Implications

Additional studies could expand this study's technique to capture the complexity and dynamics of emotional reactions in autism by using multimodal emotion identification, including physiological indications such as skin conductance [24]. Additionally, using machine learning methods might improve the prediction accuracy of AU data, improving the detection of intricate, context-specific emotional patterns in ASD [26]. A combined AU-physiological approach may eventually lead to more personalised therapies targeted to address particular sensory-social problems in real time and enhance social integration for autistic persons in a variety of contexts [27].

RECOMMENDATIONS

Prospective investigations are encouraged to focus on significantly larger samples (n > 50 per group) and longitudinal techniques that capture behaviour across multiple contexts (e.g., familiar vs. unfamiliar social partners, low- vs. high-sensory environments), recognising the existence of descriptive trends and a significant correlation between social (AU12) and sensory (AU45) indicators. To evaluate and contextualise computerised facial action unit outcomes, multimodal evaluation is particularly suggested, requiring physiological indicators (heart rate variability, skin conductance), eye-tracking, and concurrent linguistic assessments. From an intervention standpoint, the findings facilitate the creation of sensory-friendly, play-based programmes with the objective to increase spontaneous social engagement possibilities without mandating Neurotypical norms of facial expressivity, consequently corresponding with contemporary neurodiversity-affirming and personalised support frameworks.

CONCLUSIONS

The study provides insights into the use of micro-expression analysis to understand sensory and social processing in autism, highlighting the need of naturalistic observation in ASD studies. Although statistical significance was not obtained, the changes in AU12 and AU45 indicate important behavioural indicators that should be investigated further. This investigation adds to a further, more ecologically sound awareness of autism by expanding the scope of emotional analysis to include unstructured settings, advising future areas of study and possibly implementing strategies that promote social engagement and sensory regulation in autistic populations.

REFERENCES

- Shah A, Banner N, Heginbotham C, Fulford B. American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA. 8. Bechara, A., Dolan, S. and Hindes, A.(2002) Decision-making and addiction (Part II): myopia for the future or hypersensitivity to reward? Neuropsychologia, 40, 1690–1705. 9. Office of Public Sector Information (2005) The Mental Capacity Act 2005. Substance Use and Older People. 2014;21(5):9. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR. Surveillance summaries. 2020;69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sasson NJ, Morrison KE, Kelsven S, Pinkham AE. Social cognition as a predictor of functional and social skills in autistic adults without intellectual disability. Autism Research. 2020;13(2):259-70. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV, Ellsworth P. Emotion in the human face: Guidelines for research and an integration of findings. Elsevier; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S, Heemsbergen J, Jordan H, Mawhood L, et al. Austism diagnostic observation schedule: A standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. 1989;19(2):185-212. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Uljarevic M, Hamilton A. Recognition of emotions in autism: a formal meta-analysis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2013;43(7):1517-26. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masoomi M, Saeidi M, Cedeno R, Shahrivar Z, Tehrani-Doost M, Ramirez Z, et al. Emotion recognition deficits in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive meta-analysis of accuracy and response time. Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2025;3:1520854. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davidson RJ. The emotional life of your brain: How its unique patterns affect the way you think, feel, and live--and how you can change them. Penguin; 2012. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV. Facial action coding system. Environmental Psychology & Nonverbal Behavior. 1978. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Benning SD, Holtzclaw TN, Bodfish JW. Affective modulation of the startle eyeblink and postauricular reflexes in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40(7):858-69. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robertson AE, Simmons DR. The sensory experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative analysis. Perception. 2015;44(5):569-86. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh E, Whitehouse J, Waller BM. Being facially expressive is socially advantageous. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):12798. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deng L, He WZ, Zhang QL, Wei L, Dai Y, Liu YQ, et al. Caregiver-child interaction as an effective tool for identifying autism spectrum disorder: evidence from EEG analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17(1):138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baltrušaitis T, Robinson P, Morency LP. Openface: an open source facial behavior analysis toolkit. In2016 IEEE winter conference on applications of computer vision (WACV) 2016 (pp. 1-10). IEEE. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Moody CT, Laugeson EA. Social Behavior and Social Interventions for Adults on the Autism Spectrum. InHandbook of Quality of Life for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder 2022 (pp. 357-376). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Paparella T, Freeman S, Jahromi LB. Language outcome in autism: randomized comparison of joint attention and play interventions. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2008;76(1):125. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pelphrey KA, Sasson NJ, Reznick JS, Paul G, Goldman BD, Piven J. Visual scanning of faces in autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2002;32(4):249-61. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zantinge G, van Rijn S, Stockmann L, Swaab H. Physiological arousal and emotion regulation strategies in young children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(9):2648-57. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zadeh A, Chong Lim Y, Baltrusaitis T, Morency LP. Convolutional experts constrained local model for 3d facial landmark detection. InProceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops 2017 (pp. 2519-2528). [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Noldus Information Technology. (2020). Facial Action Coding System: Assessing real-time emotional responses. Noldus Information Technology.

- Chita-Tegmark M. Social attention in ASD: A review and meta-analysis of eye-tracking studies. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;48:79-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(4):231-9. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klin A, Shultz S, Jones W. Social visual engagement in infants and toddlers with autism: Early developmental transitions and a model of pathogenesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;50:189-203. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porges SW, Furman SA. The early development of the autonomic nervous system provides a neural platform for social behaviour: A polyvagal perspective. Infant Child Dev. 2011 Jan;20(1):106-18. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lory C, Kadlaskar G, McNally Keehn R, Francis AL, Keehn B . Brief report: Reduced heart rate variability in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(11):4183-90. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banos O, Comas-González Z, Medina J, Polo-Rodríguez A, Gil D, Peral J, et al. Sensing technologies and machine learning methods for emotion recognition in autism: Systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2024;187:105469. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsapanou A, Bouka A, Papadopoulou A, Vamvatsikou C, Mikrouli D, Theofila E, et al. Application of Artificial Intelligence Tools for Social and Psychological Enhancement of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2025;16(1):56. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Article Processing Timeline

| 2-5 Days | Initial Quality & Plagiarism Check |

| 15 Days |

Peer Review Feedback |

| 85% | Acceptance Rate (after peer review) |

| 30-45 Days | Total article processing time |

Journal Flyer